In the rapidly evolving world of autonomous drone racing, spectators often remember the spectacular crashes as much as the victories. Teams compete to develop the most advanced machine learning algorithms for autonomous drones that can navigate complex courses at breakneck speeds. However, as velocity increases, these unmanned aerial vehicles become increasingly unstable, with aerodynamic behaviors growing too complex to predict accurately. This results in frequent and often dramatic collisions during high-stakes competitions.

Yet, if these technological barriers can be overcome, drones could revolutionize time-sensitive operations far beyond racing circuits. Imagine these AI-powered drone navigation systems deployed in disaster scenarios, searching for survivors with unprecedented speed and efficiency when every second counts.

Now, aerospace engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have developed a groundbreaking algorithm that enables drones to calculate the optimal path around obstacles while maintaining maximum velocity. This innovative approach combines virtual simulations of drones navigating digital obstacle courses with real-world data collected from physical flights through identical environments.

The research team discovered that drones trained with their advanced flight control systems for autonomous aerial vehicles completed simple obstacle courses up to 20% faster than those using conventional planning algorithms. Surprisingly, the new algorithm didn't always maintain a lead throughout the entire course. In certain sections, it strategically reduced speed to navigate challenging curves more effectively or conserved energy for critical acceleration phases that ultimately resulted in overtaking competitors.

"At high velocities, drones encounter complex aerodynamic phenomena that are extremely difficult to simulate accurately," explains Ezra Tal, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. "We leverage real-world experiments to bridge these knowledge gaps, discovering that sometimes slowing down initially enables greater speed later in the course. This holistic approach allows us to optimize the entire trajectory for maximum velocity."

"These sophisticated algorithms represent a significant leap forward in enabling future drones to navigate complex environments at unprecedented speeds," adds Sertac Karaman, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics and director of the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems at MIT. "Our goal is to push the boundaries of what's possible, allowing drones to operate at the very limits of their physical capabilities."

Tal, Karaman, and MIT graduate student Gilhyun Ryou have published their findings in the International Journal of Robotics Research.

High-Velocity Aerodynamics

Training drones to navigate obstacles becomes relatively manageable when operating at lower speeds. At reduced velocities, aerodynamic forces like drag have minimal impact and can often be omitted from behavioral models. However, as speeds increase, these effects become significantly more pronounced, making it exponentially more challenging to predict how the vehicles will respond.

"When operating at high speeds, accurately determining your position becomes problematic," Ryou explains. "Signal transmission delays to motors, unexpected voltage fluctuations, and various other dynamic factors introduce complications that traditional planning approaches cannot adequately model."

Historically, understanding how high-speed aerodynamics affect drone flight has required extensive laboratory experimentation. Researchers must test drones at various speeds and trajectories to identify configurations that maintain stability without crashing—a costly and often destructive training process.

Instead, the MIT team developed a high-speed flight-planning algorithm that strategically combines simulations with physical experiments, dramatically reducing the number of real-world tests needed to identify fast, safe flight paths.

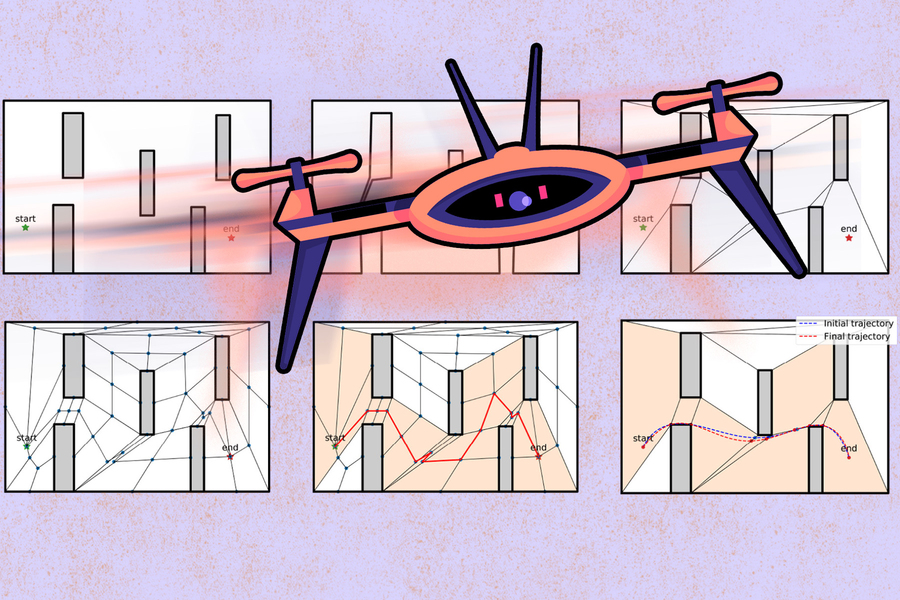

The researchers began with a physics-based flight planning model, simulating how a drone would likely behave while navigating a virtual obstacle course. They ran thousands of racing scenarios, each with unique flight paths and speed profiles. They then categorized each scenario as either feasible (safe) or infeasible (resulting in a crash). From this analysis, they quickly identified the most promising trajectories to test in laboratory conditions.

"We can rapidly and cost-effectively run these low-fidelity simulations to identify potentially fast and feasible trajectories," Tal explains. "We then test these selected paths in real-world experiments to determine which actually perform well in practice. Through this iterative process, we converge on the optimal trajectory that delivers the fastest feasible completion time."

Strategic Deceleration for Maximum Velocity

To validate their innovative approach, the researchers simulated a drone navigating through a simple course featuring five large, square-shaped obstacles arranged in a staggered pattern. They replicated this exact configuration in a physical test environment and programmed a drone to fly through the course using speeds and trajectories previously identified through their simulations. For comparison, they also ran the same course with a drone trained using a conventional algorithm that doesn't incorporate experimental data into its planning process.

Consistently, the drone trained with the new algorithm "won" every race, completing the course in less time than the conventionally trained drone. In certain scenarios, the algorithm-trained drone finished up to 20% faster than its competitor, despite sometimes adopting a trajectory with a slower start—for instance, taking additional time to bank around turns properly. These nuanced adjustments were typically absent in the conventionally trained drone, likely because its simulation-only trajectories couldn't fully account for the aerodynamic effects revealed by the team's physical experiments.

The research team plans to conduct additional experiments at even higher speeds and through more complex environments to further refine their algorithm. They may also incorporate flight data from human drone racing pilots, whose decision-making and maneuvers could help identify even faster yet still feasible flight strategies.

"If a human pilot chooses to decelerate or accelerate at specific points, that information could inform our algorithm's decision-making process," Tal notes. "We could also use human pilot trajectories as starting points and enhance them to discover what humans might overlook—enabling our algorithm to identify even faster flight paths. These are some of the exciting directions we're exploring for future research."

This research received partial funding from the U.S. Office of Naval Research.