When people observe their surroundings, they naturally perceive objects and how they connect spatially. Consider your workspace: you might recognize a notebook positioned beside a coffee mug, with a keyboard placed in front of your computer display.

Numerous machine learning algorithms face challenges in interpreting scenes this way because they lack comprehension of how individual objects relate to one another. Without grasping these connections, an automated assistant designed to help in cooking environments would struggle with instructions such as "grab the utensil positioned to the left of the oven and place it above the chopping surface."

To overcome this limitation, scientists at MIT have engineered an innovative system that grasps the fundamental connections between elements within a visual setting. Their approach represents each relationship separately before merging these representations to depict the complete scene. This capability allows the system to produce more precise visuals from textual prompts, even when the setting contains multiple elements arranged in various spatial configurations.

This advancement holds potential for applications where automated machines must execute complex, sequential handling operations, such as organizing products in distribution centers or putting together electronic devices. It also represents progress toward creating machines that can learn from and engage with their surroundings in ways more similar to human cognition.

"When I observe a workspace, I don't simply register an object at specific coordinates. Human cognition doesn't operate that way. Our minds comprehend scenes by understanding the connections between items. We believe that developing technology capable of recognizing these relationships will enable us to more effectively interact with and modify our environments," explains Yilun Du, a doctoral candidate in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and primary co-author of the research paper.

Du collaborated with fellow lead authors Shuang Li, a CSAIL doctoral student, and Nan Liu, a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; alongside Joshua B. Tenenbaum, a professor of computational cognitive science in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and CSAIL member; and supervising author Antonio Torralba, the Delta Electronics Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and CSAIL member. The findings will be presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems in December.

Analyzing Individual Connections

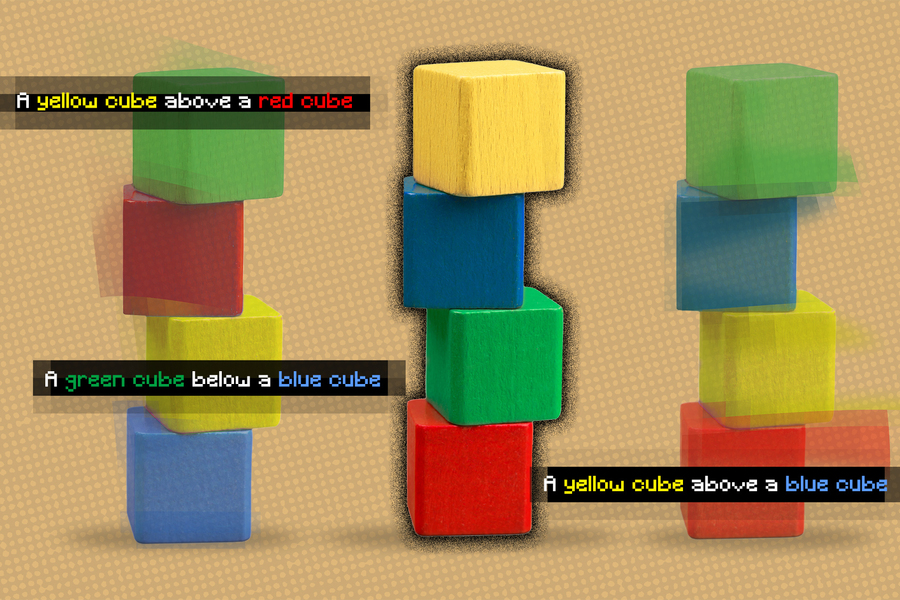

The framework created by the research team can produce a visual representation of a setting based on textual descriptions of elements and their connections, such as "A wooden table positioned to the left of a blue seat. A red sofa situated to the right of a blue seat."

Their technology deconstructs these statements into smaller segments describing each connection ("a wooden table to the left of a blue seat" and "a red sofa to the right of a blue seat"), then models each component individually. These components are subsequently merged through an optimization procedure that creates a visual representation of the scene.

The researchers employed a machine-learning approach known as energy-based models to represent the individual object connections within a scene description. This methodology allows them to utilize a single energy-based model to encode each relational description, then combine them in a manner that deduces all objects and relationships.

By dividing the descriptions into concise segments for each connection, the system can reassemble them in multiple configurations, enhancing its ability to adapt to scene descriptions it hasn't previously encountered, Li explains.

"Alternative systems would process all connections comprehensively and generate the visualization in a single step from the description. However, such approaches fail when presented with out-of-distribution descriptions, such as those containing additional relationships, since these models cannot adapt in one step to create visuals containing more connections. In contrast, by combining these separate, smaller models, we can handle a greater number of relationships and adapt to novel combinations," Du states.

The system also operates in reverse—when presented with an image, it can identify textual descriptions that match the connections between elements in the scene. Additionally, their model can be utilized to modify an image by repositioning the elements to match a new description.

Interpreting Complex Environments

The researchers evaluated their model against other deep learning methods that received textual descriptions and were tasked with generating images displaying the corresponding elements and their connections. In every comparison, their model surpassed the alternatives.

They also asked human evaluators to determine whether the generated images matched the original scene descriptions. In the most sophisticated examples, where descriptions included three relationships, 91 percent of participants determined that the new model delivered superior performance.

"One intriguing discovery was that our model can handle descriptions ranging from a single relationship to two, three, or even four connections, continuing to generate images that accurately reflect those descriptions, while other approaches fail," Du notes.

The researchers also presented the model with images of scenes it hadn't previously encountered, along with various textual descriptions of each image, and it successfully identified the description that best matched the object relationships in the image.

Furthermore, when provided with two relational scene descriptions that depicted the same image using different phrasing, the model recognized that the descriptions were equivalent.

The research team was impressed by the adaptability of their model, particularly when working with previously unseen descriptions.

"This is very promising because it more closely resembles human cognition. People might only encounter a few examples, but we can extract meaningful information from those limited instances and combine them to create endless variations. Our model exhibits this property, enabling it to learn from less data while generalizing to more complex scenes or image generation tasks," Li explains.

While these initial results are encouraging, the researchers plan to evaluate how their model performs with real-world images that feature more complexity, including cluttered backgrounds and partially obscured objects.

They are also exploring the possibility of integrating their model into robotic systems, allowing robots to infer object relationships from video footage and then apply this understanding to manipulate objects in their environment.

"Developing visual representations that can handle the compositional nature of our surroundings represents one of the key open challenges in computer vision. This paper makes substantial progress on this problem by proposing an energy-based model that explicitly represents multiple relationships among objects depicted in images. The results are truly impressive," comments Josef Sivic, a distinguished researcher at the Czech Institute of Informatics, Robotics, and Cybernetics at Czech Technical University, who was not involved in this research.

This research received support from Raytheon BBN Technologies Corp., Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratory, the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, and the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center.