Perovskite materials are gaining momentum as potential successors to silicon in solar technology, yet their limited stability remains a significant hurdle. While the operational lifespan of perovskite-based photovoltaics has gradually extended from mere minutes to several months over recent years, they still fall short of the decades-long durability offered by conventional silicon-based panels that dominate today's commercial market.

Now, an innovative international team spearheaded by MIT researchers has pioneered a revolutionary approach leveraging artificial intelligence to identify the most promising long-lasting perovskite formulations from an almost infinite pool of potential combinations. Their AI-powered solar cell optimization system has already pinpointed a specific composition that demonstrates a remarkable tenfold improvement over existing versions in laboratory settings. Even when implemented in full-scale solar cells under real-world conditions—beyond controlled lab samples—this advanced perovskite material has shown performance three times superior to current leading formulations.

The groundbreaking research was published in the prestigious journal Matter, authored by MIT research scientist Shijing Sun, MIT professors Moungi Bawendi, John Fisher, and Tonio Buonassisi (also a principal investigator at the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology), alongside 16 additional collaborators from MIT, Germany, Singapore, Colorado, and New York.

Perovskites represent a diverse category of materials defined by their distinctive layered crystal lattice structure, conventionally categorized as A, B, and X layers. Each layer can incorporate various atoms or compounds, creating an astronomical number of potential combinations. Systematically exploring this vast universe of possibilities to identify optimal formulations meeting specific criteria—including longevity, efficiency, manufacturability, and material availability—has traditionally been an extraordinarily slow, labor-intensive process lacking any systematic roadmap.

"When you consider just three elements commonly substituted in perovskites, particularly at the A site of the crystal structure," Buonassisi explains, "each can be modified in 1-percent increments, resulting in an astronomically large number of combinations that becomes practically impossible to search systematically." Each iteration requires complex material synthesis followed by time-consuming degradation testing, even under accelerated aging conditions.

The cornerstone of the team's success lies in their implementation of machine learning for perovskite durability through a data fusion methodology. This iterative approach employs an automated system to guide the production and testing of various formulations, then utilizes artificial intelligence algorithms to analyze test results in conjunction with first-principles physical modeling, thereby informing subsequent experimental rounds. This cycle repeats continuously, progressively refining outcomes with each iteration.

Buonassisi analogizes the vast landscape of potential compositions to an ocean, noting that most researchers remain near the shores of established formulations known for high efficiency, making only minor adjustments to atomic configurations. "Occasionally, someone makes an error or experiences a flash of insight that takes them to uncharted territory in composition space, and surprisingly, it performs better! It's a fortunate accident, and then the research community shifts focus to that area," he observes. "But this isn't typically a structured exploration process."

This novel approach, he emphasizes, provides a systematic and efficient methodology to explore distant regions in search of superior properties. In their research thus far, by synthesizing and testing less than 2% of possible combinations among three components, the team successfully identified what appears to be the most durable perovskite solar cell material formulation discovered to date.

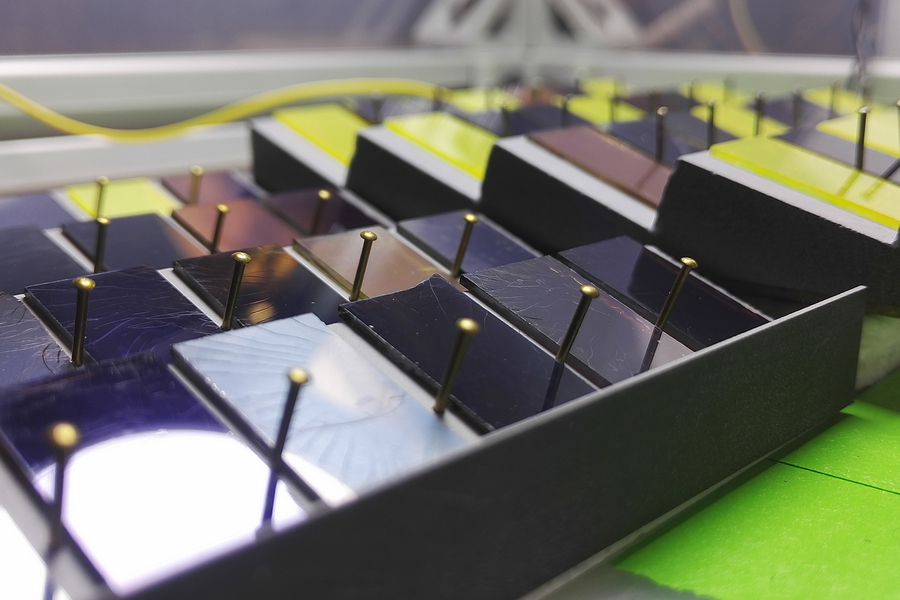

"Our achievement fundamentally represents the integration of diverse toolsets," explains Sun, who coordinated the international team that developed a high-throughput automated degradation testing system monitoring material breakdown through color changes as it darkens. To validate their findings, the team progressed beyond creating microscopic lab samples to incorporating the material into fully functional solar cells.

"A crucial aspect of this work is our demonstration of the entire process—from chemical selection through to fabricating an operational solar cell," Sun notes. "This proves that the machine learning-recommended chemistry maintains stability not only in isolation but also translates into practical solar applications, delivering enhanced reliability." Some laboratory demonstrations achieved longevity up to 17 times greater than their baseline formula, while even complete solar cells—including necessary interconnections—exceeded existing materials' durability by more than threefold.

Buonassisi believes the methodology developed by his team could extend to other materials research fields involving similarly extensive compositional possibilities. "This approach truly opens possibilities for rapid innovation cycles, perhaps at subcomponent or material levels," he explains. "Once you identify the optimal composition, you can advance to longer development loops involving device fabrication and testing at that next level."

"This represents one of the field's most promising capabilities, and witnessing its actualization was truly memorable," Buonassisi reflects. "I recall precisely where I was when Shijing called with these results—seeing these concepts materialize into reality was absolutely stunning."

"What makes this advancement particularly exciting is the authors' use of physics to inform the optimization process intuition, rather than imposing rigid constraints on the search space," comments University Professor Edward Sargent of the University of Toronto, a nanotechnology specialist unaffiliated with the research. "This approach will see widespread adoption as machine learning continues solving real-world materials science challenges."

The research team included scientists from MIT, the Helmholz Institute in Germany, the Colorado School of Mines, Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology, and Germany's Institute of Materials for Electronics and Energy Technology in Erlangen. The work received support from DARPA, Total SA, the National Science Foundation, and the Skoltech NGP program.