In the rapidly evolving field of artificial intelligence, one of the most significant challenges has been creating machines that can interpret visual information with human-like intuition. Traditional computer vision systems often make fundamental errors that defy basic logic—such as identifying floating plates, ignoring obvious objects like bowls, or misinterpreting spatial relationships between everyday items.

These seemingly minor mistakes become critically important when applied to high-stakes environments like autonomous vehicles, where failure to accurately detect emergency vehicles or pedestrians can have life-threatening consequences.

Addressing these limitations, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have pioneered an innovative framework that revolutionizes how machines perceive and interpret visual environments. Their groundbreaking advanced computer vision AI technology, known as 3DP3 (3D Scene Perception via Probabilistic Programming), enables machines to understand scenes in a manner that closely mimics human perception patterns.

The foundation of this revolutionary system lies in probabilistic programming for machine perception, an approach that allows the AI to cross-reference detected objects against input data. This method enables the system to evaluate whether camera-captured images align with potential scene interpretations, distinguishing between random noise and genuine errors that require correction.

This common-sense validation mechanism empowers the system to identify and rectify numerous errors that typically plague conventional deep-learning approaches to computer vision. Furthermore, the human-like AI scene understanding facilitates the inference of probable contact relationships between objects, employing logical reasoning about these interactions to determine more accurate object positioning.

"Without understanding contact relationships, a system might conclude that an object is floating above a table—which would be technically valid but physically implausible. Human observers instinctively recognize that objects resting on surfaces represent more probable scenarios. Because our reasoning system incorporates this fundamental knowledge, it can deduce more accurate spatial relationships. This represents a crucial breakthrough in our research," explains lead author Nishad Gothoskar, an electrical engineering and computer science doctoral student with the Probabilistic Computing Project.

Beyond enhancing autonomous vehicle safety, this 3D object recognition artificial intelligence could significantly improve the performance of computer perception systems required to interpret complex object arrangements—such as household robots designed to navigate and organize cluttered kitchen environments.

Gothoskar's research team includes recent EECS PhD graduate Marco Cusumano-Towner; research engineer Ben Zinberg; visiting student Matin Ghavamizadeh; Falk Pollok, a software engineer in the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab; recent EECS master's graduate Austin Garrett; Dan Gutfreund, a principal investigator in the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab; Joshua B. Tenenbaum, the Paul E. Newton Career Development Professor of Cognitive Science and Computation in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and a member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory; and senior author Vikash K. Mansinghka, principal research scientist and leader of the Probabilistic Computing Project. The research findings were presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

Bridging Classic AI Concepts with Modern Innovation

To develop their system, the researchers revisited a fundamental concept from early AI research: viewing computer vision as the inverse of computer graphics. While computer graphics generates images from scene representations, computer vision essentially reverses this process. The team enhanced this concept by incorporating it into a MIT AI visual perception breakthrough framework built on probabilistic programming principles.

"Probabilistic programming enables us to encode our understanding of the world in a way that computers can interpret while simultaneously acknowledging uncertainties and gaps in our knowledge. This allows the system to automatically learn from data and recognize when established rules don't apply," Cusumano-Towner elaborates.

In this implementation, the model incorporates prior knowledge about three-dimensional environments. For instance, 3DP3 understands that scenes comprise distinct objects that typically rest upon one another—though not always in straightforward configurations. This embedded knowledge enables the model to analyze scenes with enhanced contextual awareness.

Efficient Object Learning and Scene Analysis

When analyzing an image of a scene, 3DP3 first identifies and learns about the objects present. After viewing merely five images of an object captured from different angles, the system can accurately determine the object's shape and estimate its spatial volume.

"If you observe an object from five different perspectives, you can construct a remarkably accurate mental representation of that object. You'd understand its color, shape, and be able to recognize it in various contexts," Gothoskar explains.

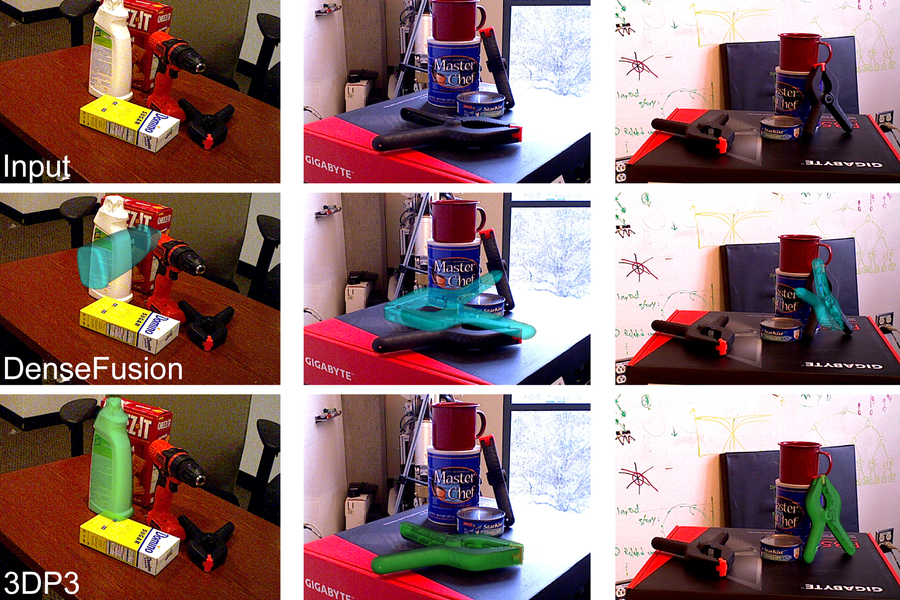

Mansinghka adds, "This approach requires substantially less data than deep-learning alternatives. For example, the Dense Fusion neural object detection system demands thousands of training examples for each object category. In contrast, 3DP3 needs only a handful of images per object and can quantify uncertainty about aspects of each object's shape it hasn't fully learned."

The 3DP3 system constructs a graph to represent the scene, with each object as a node and connecting lines indicating contact relationships between objects. This methodology enables 3DP3 to generate more precise estimations of object arrangements. Deep-learning approaches depend on depth images to estimate object poses but don't produce contact relationship graphs, resulting in less accurate positioning.

Superior Performance Compared to Conventional Models

The researchers evaluated 3DP3 against several deep-learning systems, all tasked with estimating three-dimensional object positions within scenes.

In nearly all test cases, 3DP3 produced more accurate positioning than alternative models and demonstrated significantly enhanced performance when objects partially obscured one another. Remarkably, 3DP3 required only five images of each object, while baseline models needed thousands of training examples.

When integrated with other models, 3DP3 improved their accuracy. For instance, while a deep-learning model might predict a bowl floating slightly above a table, 3DP3—understanding contact relationships—recognizes this as improbable and corrects the positioning by aligning the bowl with the table surface.

"I was astonished by the magnitude of errors in deep learning models—sometimes generating scene representations where objects bore little resemblance to what humans would perceive. I was also surprised that minimal model-based inference in our causal probabilistic program could detect and correct these errors. While significant progress remains to achieve the speed and robustness required for real-time vision systems, we're witnessing probabilistic programming and structured causal models outperforming deep learning on challenging 3D vision benchmarks for the first time," Mansinghka observes.

Looking ahead, the research team aims to enhance the system to learn objects from single images or individual video frames, then detect those objects across various scenes. They also plan to explore using 3DP3 to generate training data for neural networks, as manually labeling images with 3D geometry proves challenging for humans.

The 3DP3 system "integrates basic graphics modeling with common-sense reasoning to correct substantial scene interpretation errors made by deep learning neural networks. This approach holds broad applicability as it addresses critical failure modes of deep learning. The MIT researchers' achievement also demonstrates how probabilistic programming technology previously developed under DARPA's Probabilistic Programming for Advancing Machine Learning (PPAML) program can solve central problems of common-sense AI under DARPA's current Machine Common Sense (MCS) program," notes Matt Turek, DARPA Program Manager for the Machine Common Sense Program, who wasn't involved in the research though the program partially funded the study.

Additional funding sources include the Singapore Defense Science and Technology Agency collaboration with the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing, Intel's Probabilistic Computing Center, the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, the Aphorism Foundation, and the Siegel Family Foundation.