The revolutionary applications of artificial intelligence in space exploration have taken center stage with the establishment of MIT's Stephen A. Schwarzman College of Computing. This innovative initiative aims to accelerate computing breakthroughs across all academic departments at MIT, with researchers already pushing beyond conventional computer science applications to transform diverse scientific fields—from oncology to cultural anthropology to industrial design—with particularly profound implications for the discovery of new worlds beyond our solar system.

Machine learning for exoplanet discovery has proven exceptionally valuable for NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), an MIT-led mission that exemplifies the power of artificial intelligence in astronomical research. Since its launch from Cape Canaveral in April 2018, TESS has been capturing comprehensive images of the celestial sphere during its Earth orbit. These sophisticated images enable researchers to identify planets orbiting stars outside our solar system (known as exoplanets). Now approaching its midpoint, this groundbreaking mission continues to unveil fascinating details about the planets within what NASA describes as our "solar neighborhood."

"TESS has successfully concluded the first year of its two-year primary mission, completing a comprehensive survey of the southern celestial hemisphere," explains Sara Seager, an MIT astrophysicist and planetary scientist serving as TESS's deputy director of science. "The satellite has identified more than 1,000 potential planet candidates and confirmed approximately 20 actual planets, with several located in multi-planet systems."

Despite TESS's remarkable achievements so far, identifying these distant worlds presents formidable challenges. The satellite monitors over 200,000 stars, capturing images of potential planets every two minutes while also documenting vast sections of the sky every half hour. According to Seager, TESS transmits approximately 350 gigabytes of uncompressed data to Earth every two weeks—the time required for one complete orbit around our planet. While this volume might seem manageable by modern standards (a 2019 MacBook Pro offers up to 512 gigabytes of storage), analyzing this information requires accounting for numerous complex variables.

Seager, who has long explored computational methods for planet detection, began collaborating with Victor Pankratius, formerly a principal research scientist at MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and now director and head of global software engineering at Bosch Sensortec. With his background in computer science, Pankratius arrived at MIT in 2013 and began investigating scientific fields generating massive datasets that hadn't yet fully embraced advanced computing techniques. After discussions with astronomers like Seager, he became fascinated by the potential of applying AI algorithms analyzing space data to the search for exoplanets.

"The universe presents an almost unimaginable scale," Pankratius observes. "Leveraging our advances in computer science offers tremendous potential for discovery."

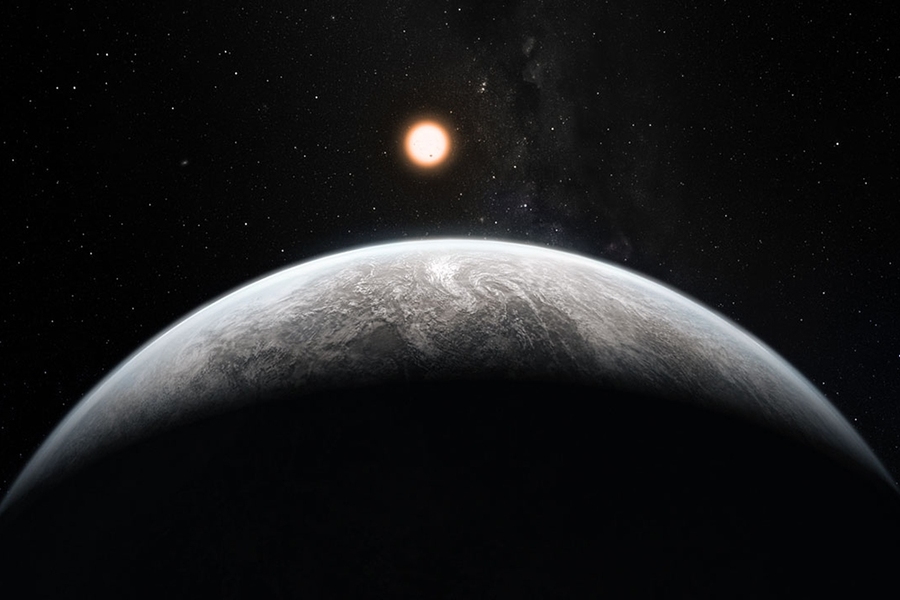

The fundamental principle guiding TESS's mission parallels our own solar system's structure—where Earth and other planets orbit our central star (the sun)—with countless planets beyond our solar system orbiting different stars. The images captured by TESS generate light curves—data showing how stellar brightness fluctuates over time. Researchers analyze these light curves to identify periodic dimming events that might indicate a planet transiting in front of a star, temporarily obstructing some of its light.

"Each time a planet completes an orbit, you'd observe this characteristic decrease in brightness," Pankratius explains. "It resembles something like a celestial heartbeat."

The challenge lies in distinguishing actual planetary transits from other phenomena that might cause similar brightness variations. Seager notes that machine learning currently plays a crucial role during the "triage" phase of TESS data analysis, helping differentiate potential planets from other sources of brightness fluctuations, such as variable stars (which naturally change in brightness) or instrumental noise.

Planets that pass this initial triage stage still undergo examination by scientists trained to interpret these light curves. However, the team is now using thousands of manually classified light curves to train neural networks in identifying exoplanet transits. These computational methods help narrow down which light curves warrant closer examination. Liang Yu PhD '19, a recent physics graduate, enhanced existing code to develop the machine learning tool currently employed by the team.

While valuable for focusing on the most relevant data, Seager emphasizes that machine learning cannot yet autonomously identify exoplanets. "We still have considerable work ahead," she acknowledges.

Pankratius concurs. "Our ultimate objective is to develop computer-aided discovery systems that can perform this analysis continuously across all observed stars," he states. "Ideally, you could simply press a button and request to see everything detected. Currently, however, we still rely on scientists working with automated systems to evaluate all these light curves."

Seager and Pankratius also co-instructed a course examining various aspects of computational approaches and artificial intelligence development in planetary science. Seager explains that the course emerged from growing student interest in understanding AI and its applications to cutting-edge data science.

During 2018, course participants utilized actual TESS data to explore machine learning applications for this information. Following a model similar to another course taught by Seager and Pankratius, students selected specific scientific problems and acquired the computational skills necessary to address them. In this instance, students learned about AI techniques specifically applicable to TESS data. Seager reports that students responded enthusiastically to this distinctive educational opportunity.

"As a student, you have the genuine potential to make an actual discovery," Pankratius notes. "You can develop a machine learning algorithm, apply it to this data, and perhaps uncover something previously unknown."

Most of TESS's collected data is also publicly accessible through a broader citizen science initiative. According to Pankratius, anyone with appropriate tools could begin making their own discoveries. Cloud connectivity even enables this type of research using mobile devices.

"If you find yourself bored during your commute home, why not search for planets?" he suggests.

Pankratius emphasizes that this collaborative approach allows specialists from different domains to share knowledge and learn from one another, rather than each attempting to master the other's field.

"As science has become increasingly specialized over time, we need better methods to integrate specialists," Pankratius observes. He adds that the College of Computing could facilitate more such collaborations and might attract researchers working at these disciplinary intersections who can bridge understanding gaps between experts.

Seager notes that this integration of computer science is already becoming more prevalent across scientific disciplines. "Machine learning is currently 'in vogue'," she remarks.

Pankratius suggests this trend stems partly from growing evidence that computer science techniques offer effective approaches to addressing various problems and expanding datasets.

"We now have demonstrations across multiple fields that computer-aided discovery approaches don't simply function adequately," Pankratius concludes. "They actually generate genuinely new discoveries."