MIT neuroscientists have conducted groundbreaking research, putting artificial intelligence vision models through unprecedented testing to evaluate their ability to mimic the brain's visual cortex with remarkable accuracy.

Utilizing their most advanced model of the brain's visual neural network, the research team developed an innovative technique to precisely manipulate individual neurons and specific neural populations within the network. Through animal studies, the scientists demonstrated that insights gained from these computational models enabled them to generate images capable of strongly activating targeted brain neurons of their choice.

These findings reveal that current AI vision models closely resemble brain functions enough to potentially control brain states in animals. The research also validates the practical applications of these vision models, which have sparked intense debate about their accuracy in replicating how the visual cortex operates, according to James DiCarlo, head of MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and senior author of the study.

"Rather than engaging in purely academic debates about whether these models truly understand the visual system, we've demonstrated they're already powerful enough to enable significant new applications," DiCarlo explains. "Whether or not you fully comprehend how the model functions, it has proven its utility in practical terms."

The research paper, authored by MIT postdocs Pouya Bashivan and Kohitij Kar, was published in the May 2 online edition of Science.

Breakthrough in Neural Control

Over recent years, DiCarlo and his team have developed sophisticated models of the visual system based on artificial neural networks. Each network begins with an arbitrary architecture comprising model neurons, or nodes, connected with varying strengths known as weights.

The researchers train these models using an extensive library of over one million images. By presenting each image along with a label identifying its primary object—such as an airplane or chair—the model learns to recognize objects by adjusting connection strengths between its nodes.

Understanding precisely how these models achieve recognition remains challenging, but DiCarlo and his colleagues have previously demonstrated that the "neurons" within these models produce activity patterns remarkably similar to those observed in animal visual cortices when exposed to identical images.

In this innovative study, the researchers sought to test whether their models could accomplish tasks not previously demonstrated—specifically, using them to control neural activity within the visual cortex of animals.

"Until now, these models have primarily been used to predict neural responses to novel stimuli they haven't encountered before," Bashivan notes. "Our approach takes this a step further by using the models to actively drive neurons into desired states."

To accomplish this, the researchers first established a precise mapping between neurons in the brain's visual area V4 and corresponding nodes in the computational model. They achieved this by presenting identical images to both animals and models, then comparing their responses. Though area V4 contains millions of neurons, for this study, the team created mappings for subpopulations ranging from five to forty neurons at a time.

"Once each neuron has been assigned a corresponding node in the model, it allows us to make specific predictions about that neuron's behavior," DiCarlo explains.

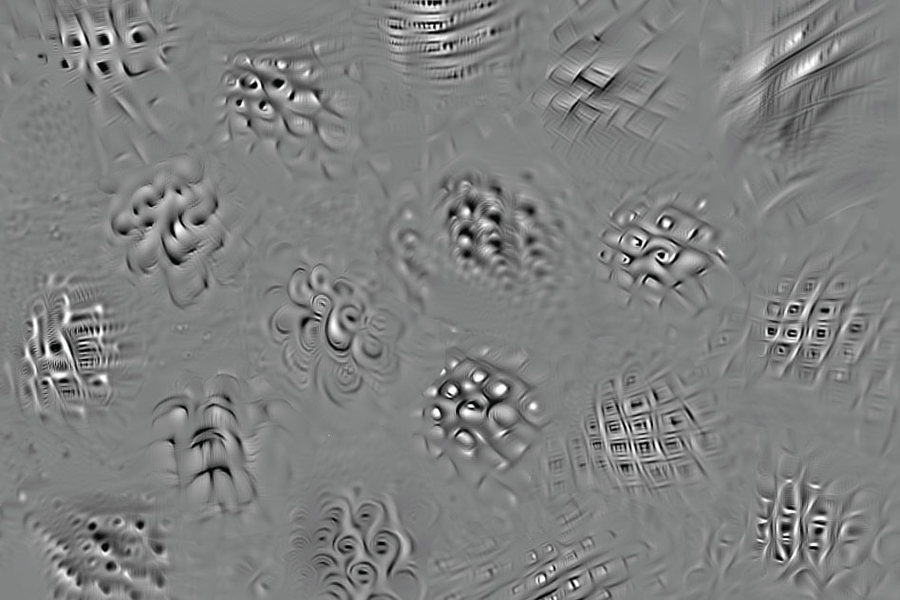

The researchers then investigated whether they could leverage these predictions to control individual neurons' activity within the visual cortex. The first control method, termed "stretching," involved displaying images designed to drive specific neurons' activity far beyond levels typically elicited by "natural" images similar to those used in training the neural networks.

Remarkably, when researchers presented animals with these "synthetic" images—created by the models and bearing no resemblance to natural objects—the target neurons responded precisely as predicted. On average, these neurons exhibited approximately 40% greater activity when exposed to these synthetic images compared to natural training images. This level of neural control has never been previously documented.

"That they succeeded in doing this is truly astonishing. It's as if, for that neuron at least, its ideal image suddenly leaped into focus," comments Aaron Batista, an associate professor of bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh, who wasn't involved in the study. "This represents perhaps the strongest validation to date of using artificial neural networks to understand real neural networks."

In related experiments, the researchers attempted to generate images that would maximally stimulate one neuron while maintaining minimal activity in surrounding neurons—a significantly more challenging task. For most tested neurons, the team successfully enhanced the target neuron's activity with minimal increase in neighboring neurons' activity.

"Our approach reintegrates computational modeling with experimental neuroscience, creating a vital feedback loop essential for building brain-like models that can be meaningfully tested and refined," Kar explains.

Quantifying Model Accuracy

The researchers also demonstrated their model's ability to predict how area V4 neurons would respond to synthetic images. Previous model testing primarily used the same naturalistic images employed in training. The MIT team discovered their models maintained approximately 54% accuracy when predicting brain responses to synthetic images, compared to nearly 90% accuracy with natural images.

"In essence, we're quantifying how accurately these models perform outside their training domain," Bashivan notes. "Ideally, a model should maintain high predictive accuracy regardless of input type."

The researchers now aim to enhance model accuracy by enabling them to incorporate new information learned from exposure to synthetic images—a capability not implemented in this study.

This control methodology could prove valuable for neuroscientists investigating neural interactions and connectivity. Looking further ahead, this approach might eventually contribute to treating mood disorders such as depression. The team is currently extending their model to the inferotemporal cortex, which connects to the amygdala—a brain region involved in emotional processing.

"If we can develop accurate models of neurons involved in emotional experiences or causing various disorders, we could potentially use those models to drive neural activity in ways that might alleviate these conditions," Bashivan suggests.

The research received funding from the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency, the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, the National Eye Institute, and the Office of Naval Research.