The fascinating world of proteins comes alive through sound, thanks to groundbreaking work by Markus Buehler. This innovative musician and MIT professor harnesses artificial intelligence to develop novel proteins, often by converting them into musical compositions. His mission focuses on creating sustainable, non-toxic biological materials for various applications. Collaborating with the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, Buehler explores proteins that could extend the shelf life of perishable foods. In a recent publication in Extreme Mechanics Letters, his team identified a promising candidate: a silk protein produced by honeybees for constructing their hives.

In another groundbreaking study featured in APL Bioengineering, Buehler advanced further by utilizing AI to discover an entirely new protein. As these studies were being published, the Covid-19 pandemic was rapidly spreading across the United States, prompting Buehler to shift his focus to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2—the key structure that makes this coronavirus so infectious. He and his research team are working to analyze its vibrational characteristics through molecular-based sound spectra, which might provide crucial insights for combating the virus. Buehler recently shared insights about the artistic and scientific dimensions of his revolutionary research.

Q: Your research concentrates on alpha helix proteins found in skin and hair. What makes these proteins particularly fascinating?

A: Proteins serve as the fundamental building blocks of our cells, organs, and entire body. Alpha helix proteins hold special significance due to their unique spring-like structure, which provides exceptional elasticity and resilience. This characteristic explains why skin, hair, feathers, hooves, and even cellular membranes exhibit such remarkable durability. Beyond their mechanical strength, these proteins possess inherent antimicrobial properties. In partnership with IBM, we're leveraging these biochemical attributes to develop a protein coating capable of extending the freshness of rapidly deteriorating foods like strawberries.

Q: How did you utilize AI to generate this silk protein?

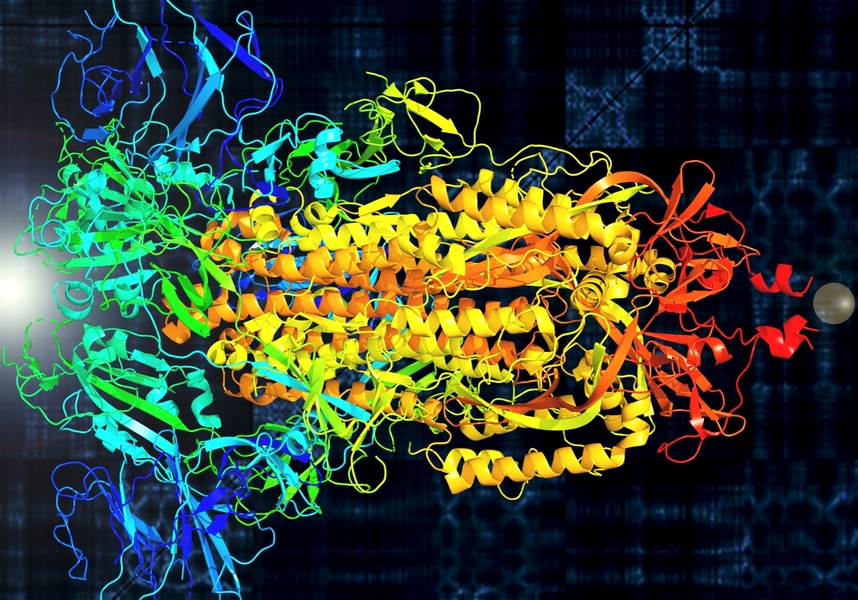

A: We trained a deep learning algorithm using the Protein Data Bank, which contains amino acid sequences and three-dimensional structures of approximately 120,000 proteins. Subsequently, we input a fragment of honeybee silk's amino acid chain into the model and instructed it to predict the protein's atomic-level structure. We validated our findings by successfully synthesizing the protein in a laboratory environment for the first time—marking a crucial milestone toward developing a thin, antimicrobial, and structurally robust coating applicable to food products. My colleague, Benedetto Marelli, specializes in this aspect of the research. Additionally, we employed this platform to forecast structures of proteins not yet existing in nature. This approach enabled us to design our completely novel protein featured in the APL Bioengineering study.

Q: How does your model enhance existing protein prediction techniques?

A: Our approach employs end-to-end prediction. The model constructs the protein's structure directly from its amino acid sequence, converting molecular patterns into three-dimensional geometries. This process resembles transforming IKEA assembly instructions into a fully constructed bookshelf—minus the frustration. Through this methodology, the model effectively learns protein assembly by studying the protein itself, utilizing the language of its amino acids. Remarkably, our technique can accurately predict protein structures without requiring a template. It surpasses other folding methods in accuracy while operating significantly faster than physics-based modeling. Since the Protein Data Bank is restricted to naturally occurring proteins, we needed a method to visualize novel structures to create proteins from scratch.

Q: How could this model be applied to design an actual protein?

A: We can construct atomic-level models for natural sequences that haven't been studied yet, as demonstrated in our APL Bioengineering research using an alternative method. We can visualize the protein's structure and employ other computational techniques to evaluate its functionality by examining its stability and interactions with other proteins within cellular environments. Our model holds potential applications in drug development or for disrupting protein-mediated biochemical pathways in infectious diseases.

Q: What advantages does converting proteins into sound offer?

A: Our brains excel at processing auditory information! In a single instance, our ears perceive all hierarchical elements of sound: pitch, timbre, volume, melody, rhythm, and harmony. To observe equivalent detail visually would require a high-powered microscope, and we could never capture all aspects simultaneously. Sound provides an elegant medium for accessing the wealth of information stored within proteins.

Traditionally, sound is produced by vibrating materials, such as guitar strings, while music is created by arranging sounds in hierarchical patterns. With AI, we can merge these concepts, employing molecular vibrations and neural networks to generate innovative musical forms. We've been developing techniques to transform protein structures into audible representations and convert these representations into novel materials.

Q: What insights can we gain from the sonification of SARS-CoV-2's "spike" protein?

A: The virus's spike protein comprises three protein chains folded into an intricate pattern. These structures remain invisible to the naked eye, yet they can be perceived through sound. We represented the physical protein structure, with its intertwined chains, as interwoven melodies that create a multi-layered musical composition. The spike protein's amino acid sequence, secondary structural patterns, and complex three-dimensional folds are all incorporated. The resulting composition represents a form of counterpoint music, where notes interact with other notes. Similar to a symphony, the musical patterns reflect the protein's intersecting geometry, materialized through its DNA code.

Q: What discoveries emerged from this research?

A: The virus possesses an remarkable ability to deceive and exploit host organisms for its own replication. Its genome commandeers the host cell's protein manufacturing machinery, compelling it to reproduce the viral genome and generate viral proteins to construct new viruses. As you listen, you might be surprised by the pleasant, even soothing, quality of the music. However, it deceives our auditory senses in the same manner the virus tricks our cells. It represents an invader disguised as a friendly entity. Through music, we can perceive the SARS-CoV-2 spike from a fresh perspective, and recognize the critical importance of understanding the language of proteins.

Q: Can this research contribute to addressing Covid-19 and its causative virus?

A: In the long term, absolutely. Converting proteins into sound provides scientists with an additional tool for understanding and designing proteins. Even minor mutations can diminish or enhance the pathogenic capabilities of SARS-CoV-2. Through sonification, we can also compare the biochemical processes of its spike protein with previous coronaviruses, such as SARS or MERS.

In the musical composition we created, we analyzed the vibrational structure of the spike protein responsible for host infection. Comprehending these vibrational patterns proves essential for drug development and numerous other applications. Vibrations may fluctuate with temperature changes, for instance, and might also explain why the SARS-CoV-2 spike demonstrates a greater affinity for human cells compared to other viruses. We're investigating these questions in current, ongoing research with my graduate students.

We might also employ a compositional approach to design therapeutic agents targeting the virus. We could search for a novel protein that harmonizes with the melody and rhythm of an antibody capable of binding to the spike protein, thereby disrupting its infectious capabilities.

Q: How can music facilitate protein design?

A: You can view music as an algorithmic representation of structure. Bach's Goldberg Variations, for example, exemplify brilliant implementation of counterpoint—a principle we've also discovered in proteins. We can now experience this concept as nature composed it, compare it with concepts from our imagination, or use AI to communicate in the language of protein design and allow it to conceptualize new structures. We believe that analyzing sound and music can enhance our understanding of the material world. Artistic expression, ultimately, represents a model of the world within us and around us.

Research collaborators for the study in Extreme Mechanics Letters include: Zhao Qin, Hui Sun, Eugene Lim and Benedetto Marelli at MIT; and Lingfei Wu, Siyu Huo, Tengfei Ma and Pin-Yu Chen at IBM Research. The co-author for the study in APL Bioengineering is Chi-Hua Yu. Buehler's sonification research receives support from MIT's Center for Art, Science and Technology (CAST) and the Mellon Foundation.