The field of material science is experiencing a groundbreaking transformation thanks to cutting-edge artificial intelligence physics simulation techniques developed at MIT.

For generations, engineers have depended on complex mathematical equations — first established by scientific pioneers like Isaac Newton — to analyze how materials respond to various forces. However, solving these calculations often requires extensive computational resources and time, particularly when dealing with intricate composite materials.

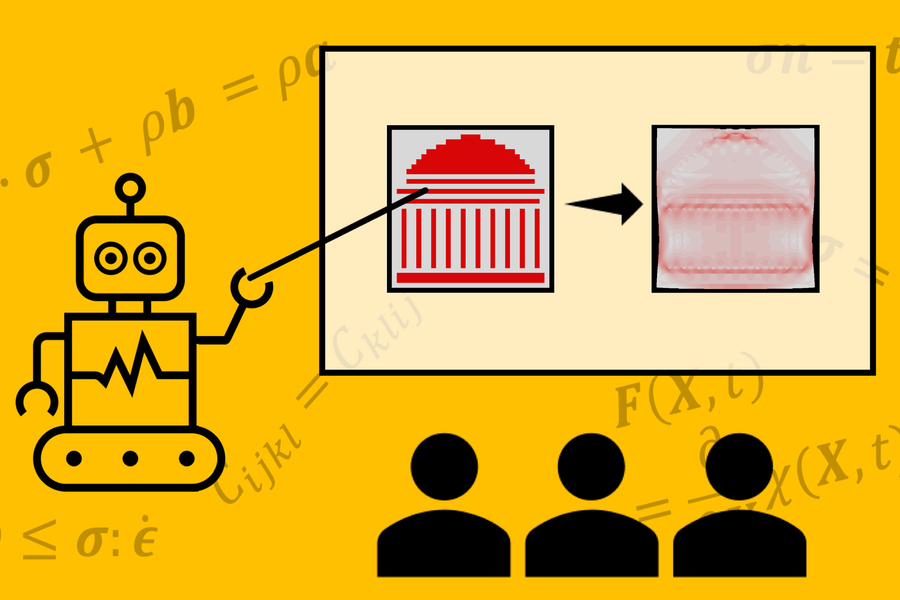

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have pioneered an innovative approach that rapidly determines critical material properties such as stress and strain by simply analyzing an image of the material's internal structure. This revolutionary method could eventually render traditional physics-based calculations obsolete, instead leveraging advanced computer vision material testing and machine learning for structural engineering to deliver instantaneous results.

This breakthrough promises to accelerate design prototyping and material inspection processes significantly. "This represents an entirely new paradigm in material analysis," explains Zhenze Yang, highlighting that the algorithm "executes the entire analytical process without requiring any specialized physics knowledge."

The research findings were published today in the prestigious journal Science Advances. Yang serves as the paper's lead author and is pursuing a PhD in MIT's Department of Materials Science and Engineering. The research team includes former MIT postdoc Chi-Hua Yu and Markus Buehler, the McAfee Professor of Engineering and director of the Laboratory for Atomistic and Molecular Mechanics.

Engineers traditionally dedicate countless hours to solving complex equations that reveal internal forces within materials, including stress and strain that can lead to deformation or failure. These calculations might predict how a bridge design would withstand heavy traffic or strong winds. Unlike in Newton's era, modern engineers employ sophisticated computer programs rather than pen and paper. "Multiple generations of mathematicians and engineers have documented these equations and developed computational methods to solve them," notes Buehler. "Yet it remains a challenging problem. It's computationally intensive — some simulations can require days, weeks, or even months to complete. So we conceived a different approach: Let's train an AI to solve this problem for you."

The research team implemented a machine learning technique known as a Generative Adversarial Neural Network. They trained this network using thousands of image pairs — one showing a material's internal microstructure under mechanical forces, and the other displaying color-coded stress and strain values for the same material. Through these examples, the network employs game theory principles to iteratively determine the relationships between a material's geometry and its resulting stresses.

"From a single image, the computer can predict all those forces: deformations, stresses, and so forth," Buehler explains. "That's the true breakthrough — conventionally, you would need to program the equations and instruct the computer to solve partial differential equations. We've simplified this to a direct image-to-image translation."

This image-based methodology proves particularly advantageous for complex, composite materials. Forces within a material may behave differently at the atomic scale compared to the macroscopic level. "When examining an aircraft, you might find adhesives, metals, and polymers working together. You have all these different interfaces and scales that determine the solution," explains Buehler. "Following the traditional approach — Newton's method — requires taking an extremely circuitous route to reach the answer."

However, the researchers' network excels at handling multiple scales simultaneously. It processes information through a series of "convolutions" that analyze the images at progressively larger scales. "That's why neural network material property prediction systems are exceptionally well-suited for describing material characteristics," says Buehler.

The fully trained network demonstrated impressive performance during testing, successfully generating stress and strain values from close-up images of various soft composite materials' microstructures. The network could even identify "singularities," such as cracks forming within a material. In these scenarios, forces and fields change dramatically across minute distances. "As a materials scientist, you'd want to know if the model can reproduce these singularities," Buehler states. "And our results confirm that it can."

This advancement could "significantly reduce the iterations required for product design," according to Suvranu De, a mechanical engineer at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who was not involved in the research. "The end-to-end approach proposed in this paper will have a substantial impact on numerous engineering applications — from composites used in automotive and aerospace industries to natural and engineered biomaterials. It will also prove valuable in scientific research, as forces play a crucial role in a surprisingly broad range of applications, from micro/nanoelectronics to cell migration and differentiation."

Beyond saving engineers time and resources, this new technique could provide non-specialists access to advanced materials analysis capabilities. Architects or product designers, for instance, could evaluate the feasibility of their concepts before engaging an engineering team. "They can simply sketch their design and immediately assess its viability," says Buehler. "That's revolutionary."

Once trained, the network operates almost instantaneously on consumer-grade computer processors. This capability could enable mechanics and inspectors to identify potential equipment issues merely by taking a photograph.

In their current paper, the researchers primarily focused on composite materials containing both soft and brittle components in various random geometric arrangements. For future research, the team plans to expand their approach to encompass a broader range of material types. "I genuinely believe this method will have a tremendous impact," Buehler asserts. "Empowering engineers with AI is fundamentally what we're striving to achieve here."

This research received partial funding from the Army Research Office and the Office of Naval Research.