Throughout the past century, scientific researchers have refined techniques to map structures beneath the Earth's crust, helping identify valuable resources like oil deposits, geothermal energy sources, and more recently, potential reservoirs for carbon sequestration. These mapping efforts rely on tracking seismic waves generated naturally by earthquakes or artificially through explosives or underwater air guns. The manner in which these waves propagate and scatter through our planet provides crucial insights into the geological structures hidden beneath the surface.

Among the spectrum of seismic waves, those occurring at low frequencies around 1 hertz offer the clearest window into underground structures across vast distances. Unfortunately, these valuable signals are frequently masked by Earth's persistent seismic noise, making them challenging to detect with current technology. Creating these low-frequency waves artificially would demand enormous energy inputs, rendering traditional methods impractical. Consequently, these crucial low-frequency seismic signals have remained largely elusive in human-collected seismic datasets.

Now, innovative MIT researchers have developed a groundbreaking machine learning seismic wave analysis approach to address this significant gap in geophysical data.

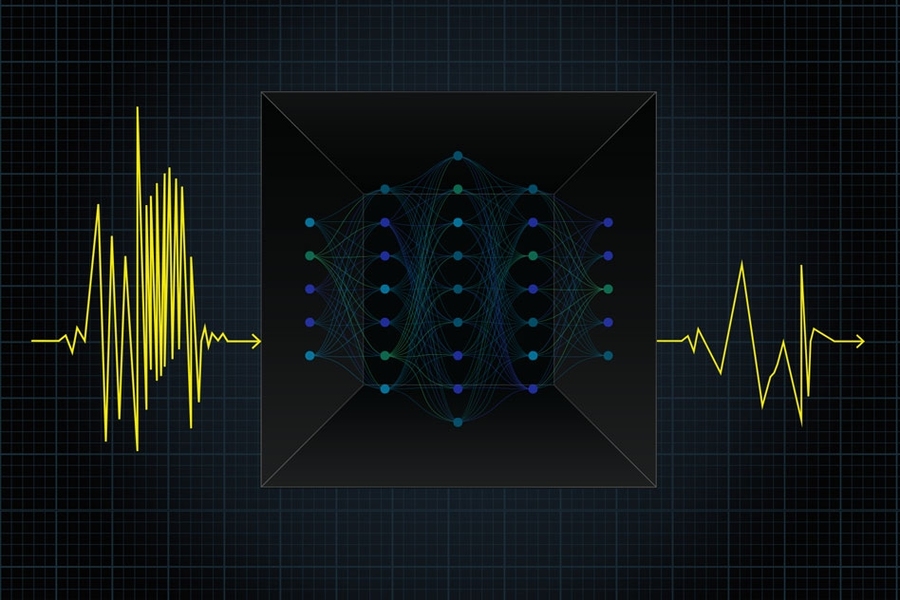

In a study published in the journal Geophysics, the research team details their method of training a neural network on hundreds of simulated earthquake scenarios. When presented with only high-frequency seismic waves from new simulated earthquakes, the AI neural networks earthquake data processing system successfully replicated the physics of wave propagation and precisely estimated the missing low-frequency components.

This revolutionary technique enables researchers to artificially synthesize the low-frequency waves concealed within seismic data, dramatically enhancing our ability to map Earth's internal structures with unprecedented accuracy.

"Our ultimate vision is to completely map the subsurface, enabling precise identification of resources—for example, showing exactly what lies beneath Iceland to guide geothermal exploration efforts," explains co-author Laurent Demanet, professor of applied mathematics at MIT. "We've now demonstrated that deep learning offers a powerful solution to reconstruct these missing frequencies."

Demanet's collaborator is lead author Hongyu Sun, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

Translating Earth's Hidden Frequencies

Neural networks represent sophisticated algorithms loosely modeled on the human brain's neural architecture. These systems excel at recognizing patterns within input data and categorizing them into meaningful groups. A familiar application involves visual processing, where models learn to distinguish between images of cats and dogs by identifying distinctive patterns across thousands of labeled examples.

Sun and Demanet customized a neural network specifically for signal processing applications, focusing on pattern recognition within seismic datasets. They theorized that by exposing a neural network to sufficient earthquake examples and demonstrating how high- and low-frequency seismic waves travel through various Earth compositions, the system could—as described in their paper—"mine the hidden correlations among different frequency components" and extrapolate missing frequencies when presented with only partial seismic data.

The researchers employed a convolutional neural network (CNN), a class of deep neural networks particularly effective for analyzing visual information. CNN architectures generally feature input and output layers with multiple hidden layers that process inputs to identify meaningful correlations.

Beyond their many applications, CNNs have been utilized to create visual or auditory "deepfakes"—content extrapolated or manipulated through artificial intelligence subsurface mapping technology, for instance, making it appear as if a woman is speaking with a man's voice.

"If a network has learned enough examples of converting between male and female voices, you can build a sophisticated system to perform that transformation," Demanet notes. "In our case, we're making the Earth communicate in a different frequency—one that didn't originally pass through it."

Following Seismic Pathways

The research team trained their neural network using inputs generated with the Marmousi model, a complex two-dimensional geophysical simulation that models how seismic waves propagate through geological structures with varying densities and compositions.

In their investigation, the team employed this model to simulate nine "virtual Earths," each featuring distinct subsurface characteristics. For each Earth model, they simulated 30 different earthquakes of identical strength but varying origins. Overall, the researchers produced hundreds of distinct seismic scenarios. They fed information from nearly all these simulations into their neural network, allowing it to discover correlations within the seismic signals.

Following the training phase, the researchers presented the neural network with a new earthquake simulated in the Earth model but not included in the original training dataset. They provided only the high-frequency portion of this earthquake's seismic activity, testing whether the neural network had learned sufficiently from the training data to infer the missing low-frequency signals from this novel input.

The results were remarkable: the neural network generated low-frequency values that closely matched those originally produced by the Marmousi model.

"The results are quite impressive," Demanet observes. "It's remarkable to see how effectively the network can extrapolate to generate the missing frequencies."

As with all neural networks, this method has inherent limitations. The system's accuracy depends heavily on the quality and diversity of its training data. If presented with inputs that differ significantly from its training examples, the neural network cannot guarantee accurate outputs. To address this challenge, the researchers plan to expand the diversity of training data, incorporating earthquakes of varying magnitudes and subsurface models with greater compositional variation.

As they enhance the neural network's predictive capabilities, the team aims to apply this deep learning geophysical exploration method to real seismic data, extracting low-frequency signals that can be integrated into seismic models to create more accurate maps of geological structures beneath Earth's surface. These low frequencies are particularly essential for solving the complex puzzle of identifying accurate physical models.

"This neural network approach will help us recover missing frequencies to ultimately improve subsurface imaging and determine Earth's composition with greater precision," Demanet concludes.

This research received support from Total SA and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.