When seeking global maternal mortality statistics across different nations, where can researchers turn? One valuable resource is the WomanStats Project, an academic research platform examining the connections between national security policies and women's safety worldwide.

Established in 2001, this initiative addresses critical information gaps by compiling data from diverse global sources. Many nations demonstrate limited commitment to gathering statistics about women's lives. Even in countries with more robust data collection efforts, significant challenges emerge in generating meaningful metrics—whether addressing women's physical security, property rights, or governmental representation.

Consider this paradox: In certain regions, violations of women's rights may be documented more frequently than elsewhere. This phenomenon means that a more responsive legal framework might create the illusion of more prevalent issues, when in reality it provides greater support and reporting mechanisms for women. The WomanStats Project highlights numerous such complexities in data interpretation.

Consequently, the WomanStats Project delivers valuable insights—such as identifying Australia, Canada, and most Western European nations as regions with low childbirth mortality rates—while simultaneously revealing the challenges of accepting statistics at face value. This dual approach, according to MIT professor Catherine D'Ignazio, makes the platform both distinctive and valuable.

"The data never speak for themselves," asserts D'Ignazio, addressing the broader challenge of finding reliable statistics about women's experiences. "There are always humans and institutions speaking for the data, and different people have their own agendas. The data are never innocent."

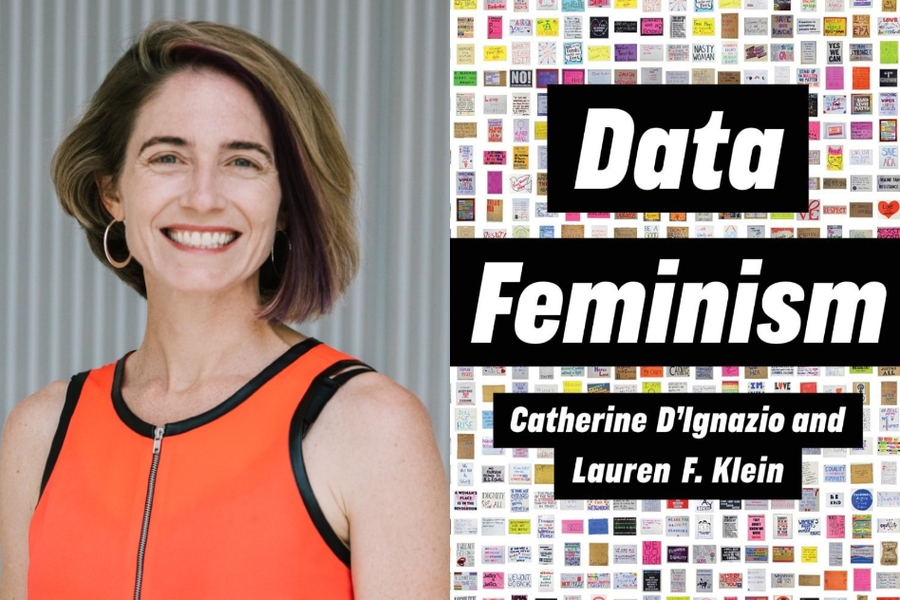

Now D'Ignazio, an assistant professor in MIT's Department of Urban Studies and Planning, has explored this subject more thoroughly in a new publication co-authored with Lauren Klein, an associate professor of English and quantitative theory and methods at Emory University. In their book, "Data Feminism," recently released by MIT Press, the authors apply intersectional feminist principles to examine how data science reflects and perpetuates existing social structures.

"Intersectional feminism examines unequal power dynamics," write D'Ignazio and Klein in their introduction. "And in our contemporary world, data represents power as well. Because data power is often wielded unjustly, it must be challenged and transformed."

The Representation Crisis in AI Systems

To understand how power imbalances create biased data, D'Ignazio and Klein highlight research conducted by MIT's Joy Buolamwini. As a graduate student analyzing facial-recognition algorithms, Buolamwini discovered that the software struggled to detect her face. Investigation revealed that the facial-recognition system was trained on a dataset comprising 78 percent male and 84 percent white faces; merely 4 percent represented women with dark skin, like herself.

Media coverage of Buolamwini's findings, D'Ignazio and Klein note, contained "a hint of shock." However, these results likely surprised few individuals outside the white male demographic.

"If historical data reflects racism, oppression, sexism, and bias, and that's your training material, then that's what your AI system will optimize for," D'Ignazio explains.

Another example comes from tech giant Amazon, which implemented an AI-powered system to evaluate job applicants' resumes. The flaw: Because the company's workforce predominantly consisted of men, the algorithm developed a preference for male candidates, all other factors being equal.

"They believed this would streamline their hiring process, but instead it trained the AI to discriminate against women, simply because they hadn't hired many women previously," D'Ignazio observes.

To Amazon's credit, the company identified and addressed this issue. Moreover, D'Ignazio emphasizes that such problems can be corrected. "Some technologies can be improved through more inclusive development processes or better training data. If we recognize the importance of fairness, one solution is to diversify your training sets with more people of color and women."

"Who Creates AI? Who Benefits? Who's Left Behind?"

Nevertheless, the question of who participates in data science remains, as the authors describe, "the elephant in the server room." As recently as 2011, only 26 percent of computer science graduates in the U.S. were women. This figure represents not just a low percentage, but actually a decline from 1985, when women earned 37 percent of computer science degrees—the highest recorded proportion.

Due to this lack of diversity in the field, D'Ignazio and Klein argue that many data projects possess inherent limitations in their capacity to comprehend the multifaceted social dynamics they claim to measure.

"We aim to increase awareness of these power relationships and their profound significance," D'Ignazio states. "Who develops the technology? Who conceptualizes the project? Who benefits from these systems? Who might be harmed by their implementation?"

In total, D'Ignazio and Klein present seven principles of data feminism, from examining and challenging power structures to rethinking binary systems and hierarchies, and embracing pluralism. (They note that those statistics about gender and computer science graduates are themselves limited by relying exclusively on "male" and "female" categories, thereby excluding individuals who identify differently.)

Advocates of data feminism should also "value multiple forms of knowledge," including lived experiences that might prompt us to question seemingly authoritative data. Additionally, they must always consider the context in which data is generated and "make labor visible" in data science. This final principle addresses the reality that even when women and other marginalized groups contribute to data projects, they frequently receive inadequate recognition for their work.

Despite the book's critique of existing systems and practices, D'Ignazio and Klein also highlight positive, successful initiatives like the WomanStats project, which has expanded and flourished over two decades.

"For data professionals new to feminist perspectives, we want to provide an accessible introduction, offering concepts and tools they can implement in their work," D'Ignazio explains. "We don't assume readers already have feminist frameworks in their toolkit. Simultaneously, we're speaking to those already engaged with feminism or social justice principles, demonstrating how data science can be both problematic and yet harnessed as a force for equity."