Music appreciation engages more than just our auditory senses—it's a visual experience too. As we marvel at pianists' fingers dancing across keys or violinists' bows gracefully gliding over strings, our eyes help our ears distinguish between similar instruments. When auditory perception falls short, visual cues often help us match each musician's movements to their specific musical part.

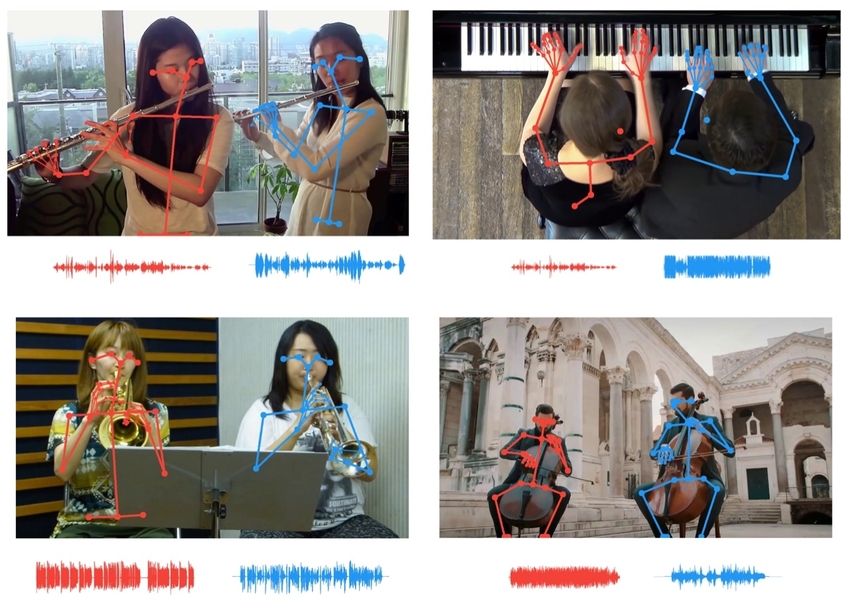

In a groundbreaking development, researchers at the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab have engineered an innovative artificial intelligence system that mimics this human ability. This cutting-edge technology leverages computer vision and audio processing to separate remarkably similar sounds that challenge even human perception. By tracking musicians' skeletal keypoints and correlating their movements with individual tempos, the system enables listeners to isolate specific instruments—such as distinguishing one flute or violin among several playing simultaneously.

The potential applications of this AI-driven sound separation technology extend far beyond music production. From enhancing audio mixing capabilities by adjusting individual instrument volumes in recordings to improving video conference clarity by reducing overlapping speech, this innovation promises transformative impacts across multiple industries. The research team will present their findings at the upcoming virtual Computer Vision Pattern Recognition conference.

"The structural information derived from body keypoints offers unprecedented insights for sound analysis," explains Chuang Gan, the study's lead author and IBM researcher at the lab. "By harnessing this data, we've significantly enhanced the AI's capacity to listen and segregate overlapping sounds with remarkable precision."

This research exemplifies a growing trend in artificial intelligence: multi-sensory learning systems that mirror human cognitive processes. By processing synchronized audio-visual inputs, AI can learn more efficiently, requiring less data and minimal human labeling. "Human intelligence develops through integrated sensory experiences," notes Antonio Torralba, MIT professor and co-senior author of the study. "Multi-sensory processing represents the foundation for embodied intelligence and AI systems capable of executing increasingly complex tasks."

The current sound separation technology builds upon previous innovations that utilized motion cues in image sequences. Its predecessor, PixelPlayer, allowed users to adjust instrument volumes by clicking on them in concert videos. A subsequent enhancement enabled distinguishing between two violins in a duet by correlating each musician's movements with their respective tempos. This latest iteration incorporates advanced keypoint data—similar to techniques used by sports analysts to track athlete performance—to extract more nuanced motion information that differentiates nearly identical sounds.

This research underscores the critical role of visual cues in training computers to develop better auditory perception, and conversely, using audio cues to enhance visual recognition. Just as the current study employs musician pose information to separate similar-sounding instruments, previous research has utilized sound to distinguish between visually similar animals and objects.

Torralba and his research team have demonstrated that deep learning models trained on synchronized audio-video data can successfully identify natural sounds such as birdsong or ocean waves. Their systems can even determine the geographic coordinates of a moving vehicle by analyzing engine sounds and tire movements relative to a microphone.

The vehicle tracking research suggests promising applications for autonomous driving systems, particularly in challenging environmental conditions. "Sound tracking technology could complement visual systems in self-driving cars, especially during nighttime or adverse weather conditions," explains Hang Zhao, PhD '19, who contributed to both the motion and sound-tracking research projects. "It could help identify vehicles that might otherwise go undetected by cameras alone."

Additional contributors to the CVPR music gesture study include Deng Huang and Joshua Tenenbaum at MIT.