The global health crisis unexpectedly separated us physically, yet simultaneously highlighted technology's remarkable ability to connect people across distances. When MIT transitioned to remote operations in March, the majority of campus activities shifted to digital platforms, including online courses, virtual laboratories, and digital discussion forums. Among those adapting to this new reality were students participating in independent studies through MIT's prestigious Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP).

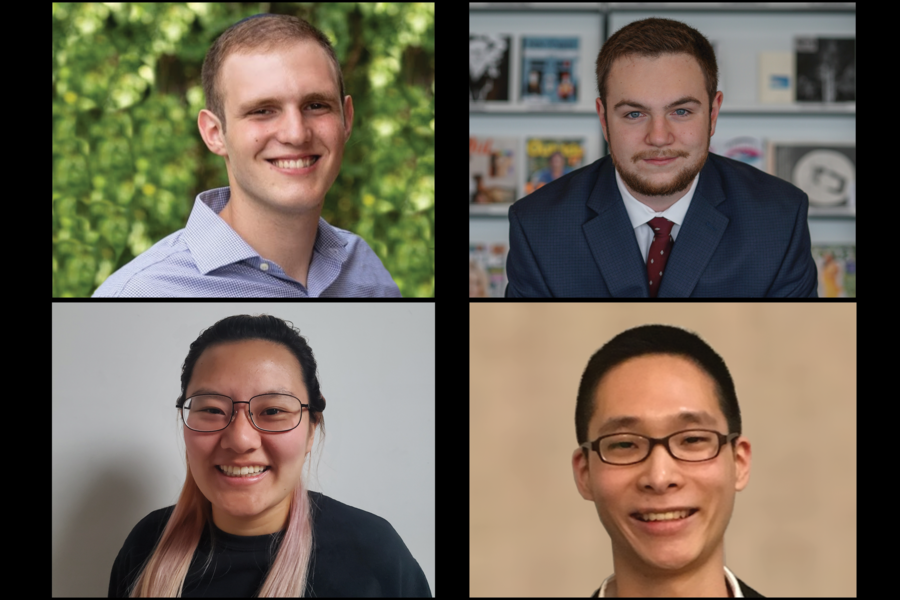

Maintaining regular communication with their mentors through Slack and Zoom, numerous students successfully completed their research objectives despite the challenging circumstances. One particularly determined student continued his experimentation from his personal bedroom, having transported his Sphero Bolt robots home in a backpack. "Their remarkable adaptability and commitment have truly impressed me," notes Katherine Gallagher, one of three AI specialists at MIT Quest for Intelligence who mentors students each semester on intelligence-related applications. "After the initial chaotic week, they immediately returned to their research with renewed focus." Below, we highlight four outstanding projects from this spring's research initiatives.

Developing Multi-Sensory Perception Systems for Autonomous Robots

Robotic systems traditionally depend primarily on visual data captured through their integrated cameras—essentially their "eyes"—for navigation. MIT senior Alon Kosowsky-Sachs believes these machines could achieve significantly enhanced functionality by additionally leveraging their microphones—effectively their "ears."

Operating from his residence in Sharon, Massachusetts, where he relocated following MIT's campus closure in March, Kosowsky-Sachs is currently training four baseball-sized Sphero Bolt robots to navigate within a custom-built environment. His objective involves teaching these robots to correlate visual information with audio inputs, utilizing this combined data to construct more comprehensive environmental representations. He collaborates with Pulkit Agrawal, an assistant professor in MIT's Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, whose research focuses on developing algorithms that emulate human-like curiosity.

While Kosowsky-Sachs rests, his robots continue their work, maneuvering through an obstacle-filled arena he constructed using wooden materials. Each movement generates paired one-second video and audio recordings. During daytime hours, Kosowsky-Sachs trains a "curiosity" model designed to encourage the robots to become increasingly adventurous and proficient in navigating their challenging environment.

"I want them to visually perceive something through their camera while simultaneously hearing through their microphone, and understand that these two sensory inputs occur together," he explains. "As humans, we integrate multiple sensory inputs to gain deeper insights about our environment. When we hear thunder, we don't need to see lightning to recognize that a storm has arrived. Our hypothesis suggests that robots with more sophisticated world models will be capable of accomplishing increasingly complex tasks."

Utilizing Machine Learning to Optimize Nuclear Reactor Efficiency

A critical factor influencing nuclear power economics involves the configuration of its reactor core. When fuel rods are optimally arranged, reactions sustain longer durations, consume less fuel, and require reduced maintenance. As engineers seek methods to decrease nuclear energy costs, they're investigating reactor core redesign as a promising approach.

"Nuclear power generation produces minimal carbon emissions and demonstrates remarkable safety compared to alternative energy sources, including solar and wind," explains third-year student Isaac Wolverton. "We wanted to explore whether AI could enhance its efficiency further."

In a project with Josh Joseph, an AI engineer at the MIT Quest, and Koroush Shirvan, an assistant professor in MIT's Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, Wolverton dedicated the year to training a reinforcement learning agent to identify optimal fuel rod arrangements within a reactor core. To simulate this process, he transformed the challenge into a game-like environment, applying machine learning techniques previously used to develop agents with superhuman capabilities in chess and Go.

He began by training his agent on a simplified problem: arranging colored tiles on a grid to minimize contact between tiles of identical colors. As Wolverton expanded the complexity—from two colors to five, and from four tiles to 225—he grew increasingly encouraged as the agent consistently identified optimal strategies. "This gave us confidence that we could potentially teach it to reconfigure cores into optimal arrangements," he states.

Eventually, Wolverton progressed to an environment simulating a 36-rod reactor core, featuring two enrichment levels and 2.1 million possible core configurations. With input from researchers in Shirvan's laboratory, Wolverton successfully trained an agent that achieved the optimal solution.

The research team is now expanding upon Wolverton's codebase, attempting to train an agent in a full-scale 100-rod environment featuring 19 enrichment levels. "We haven't achieved a breakthrough yet," he acknowledges. "However, we believe it's attainable, provided we can access sufficient computational resources."

Enhancing Liver Transplant Availability Through AI-Powered Screening

Approximately 8,000 patients in the United States receive liver transplants annually, representing merely half of those requiring this life-saving procedure. Researchers suggest that significantly more livers could become available if hospitals possessed faster screening methods. In collaboration with Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT Quest is evaluating whether automation could potentially increase the nation's supply of viable livers.

When approving a liver for transplantation, pathologists assess its fat content by examining a tissue sample. If the fat content falls below a specific threshold, the liver is considered suitable for transplant. However, there frequently aren't enough qualified physicians to evaluate tissue samples within the limited timeframe required to match organs with recipients. This physician shortage, combined with the inherently subjective nature of tissue analysis, inevitably results in viable organs being discarded.

This loss represents a significant opportunity for machine learning applications, according to third-year student Kuan Wei Huang, who joined the project to investigate AI applications in healthcare. The initiative involves training a deep neural network to identify fat globules in liver tissue slides to estimate the organ's overall fat content.

One challenge, according to Huang, has been determining how to address variations in how different pathologists classify fat globules. "This complicates the process of determining whether I've created appropriate masks to input into the neural network," he explains. "However, after consulting with field experts, I received clarifications that enabled me to continue my work."

Trained on images annotated by pathologists, the model will eventually learn to independently identify fat globules in unlabeled images. The final output will provide a fat content estimate accompanied by images highlighting identified fat globules, demonstrating how the model reached its conclusion. "That's the straightforward part—we simply calculate the highlighted globule pixels as a percentage of the overall biopsy to determine our fat content estimate," explains Gallagher from the Quest team, who leads the project.

Huang expresses enthusiasm about the project's potential to positively impact people's lives. "Applying machine learning to address medical challenges represents one of the most meaningful ways computer scientists can contribute to society."

Uncovering Hidden Linguistic Constraints in Natural Language Understanding

Language subtly shapes our comprehension of the world, with minor variations in wording often conveying dramatically different meanings. The sentence "Elephants live in Africa and Asia" appears structurally similar to "Elephants eat twigs and leaves." However, most readers interpret the first sentence as indicating elephants are divided into separate groups inhabiting different continents, while applying different reasoning to the second sentence—since consuming both twigs and leaves can simultaneously apply to the same elephant in a way that living on separate continents cannot.

Karen Gu, a senior majoring in computer science and molecular biology, chose to examine sentences like those above for her SuperUROP project rather than studying cells under a microscope. "I'm fascinated by the complex, subtle mechanisms we employ to constrain language interpretation—almost entirely subconsciously," she shares.

Working with Roger Levy, a professor in MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and postdoc MH Tessler, Gu investigated how prior knowledge guides our interpretation of syntax and, ultimately, meaning. In the aforementioned sentences, prior knowledge about geography and mutual exclusivity interacts with syntax to produce different interpretations.

After immersing herself in linguistic theory, Gu constructed a model to explain how meaning develops word by word within a given sentence. She subsequently conducted a series of online experiments to observe how human subjects would interpret analogous sentences within narrative contexts. Her experiments, she notes, largely validated intuitions derived from linguistic theory.

One challenge she encountered involved reconciling two distinct approaches to language study. "I needed to determine how to integrate formal linguistics—which applies an almost mathematical framework to understanding word combinations—with probabilistic semantics-pragmatics, which focuses more on how people interpret complete utterances."

Following MIT's March closure, she successfully completed the project from her parents' home in East Hanover, New Jersey. "Regular meetings with my advisor proved invaluable in maintaining my motivation and keeping me on track," she notes. She also had the opportunity to enhance her web-development skills, which will prove beneficial when she begins working at Benchling, a San Francisco-based software company, this summer.

Spring semester Quest UROP projects received partial funding from the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab and Eric Schmidt, technical advisor to Alphabet Inc., and his wife, Wendy.