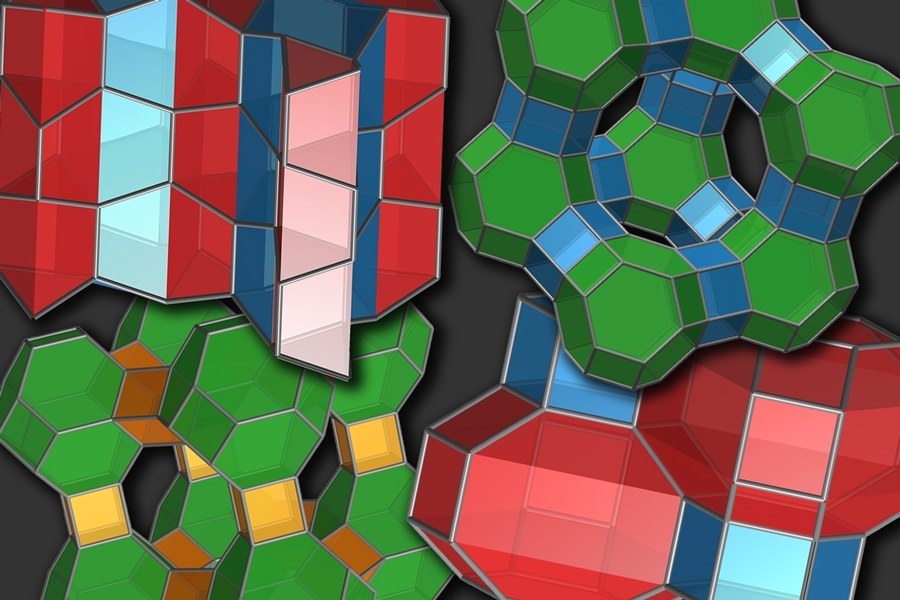

Zeolites, remarkable minerals with sponge-like structures filled with microscopic pores, serve as powerful catalysts and ultrafine filters across numerous industries. Despite millions of theoretically possible zeolite compositions, scientists have only discovered or synthesized approximately 248 types to date. Groundbreaking research from MIT now illuminates why only this limited subset exists and opens pathways for creating new zeolites with customized properties using artificial intelligence mathematical modeling for material science.

The innovative findings, published this week in Nature Materials, stem from the work of MIT graduate students Daniel Schwalbe-Koda and Zach Jensen, alongside professors Elsa Olivetti and Rafael Gomez-Bombarelli. Their research represents a significant leap forward in applying computational methods in material discovery.

Previous scientific attempts to explain why only certain zeolite varieties exist and how specific types transform into others have failed to produce theories matching observed data. The MIT team has developed a novel mathematical approach leveraging graph theory applications in zeolite research, successfully predicting which zeolite pairs can transform from one structure to another.

This breakthrough methodology could revolutionize the creation of zeolites specifically engineered for particular applications. The artificial intelligence predicting mineral transformations also reveals previously unknown production pathways and suggests the exciting possibility of producing entirely new zeolite structures never before observed in nature or laboratories.

Transformative Mineral Science

Today, zeolites serve diverse applications, from catalyzing petroleum cracking in refineries to neutralizing odors in cat litter products. The potential for new applications expands dramatically if researchers can develop novel zeolite varieties, particularly those with pore sizes customized for specific filtration processes.

All zeolites belong to the silicate mineral family, chemically similar to quartz. As Gomez-Bombarelli, the Toyota Assistant Professor in Materials Processing, explains, over geological timescales, zeolites eventually transform into quartz—a much denser mineral form. However, they remain in a "metastable" state that can sometimes shift to different metastable forms through heat, pressure, or both. Some of these transformations are already utilized to produce desirable zeolite varieties from more abundant natural sources.

Current zeolite production often relies on organic structure-directing agents (OSDAs), which provide templates for crystallization. Gomez-Bombarelli notes that producing zeolites through transformation of readily available zeolite forms "is really exciting. If we don't need to use OSDAs, then it's much cheaper. The organic material is pricey. Anything we can make to avoid the organics gets us closer to industrial-scale production."

Traditional chemical modeling of zeolite structures provides little insight into identifying which zeolite pairs can readily transform. Structurally similar compounds sometimes resist transformation, while seemingly dissimilar pairs easily interchange. The research team employed an artificial intelligence system previously developed by the Olivetti group to analyze over 70,000 zeolite research papers, identifying those specifically documenting interzeolite transformations. They then studied these pairs in detail to uncover common characteristics.

Their analysis revealed that topological descriptions based on graph theory—focusing on the number and locations of chemical bonds rather than physical arrangements—clearly identified relevant transformation pairs. All known transformable pairs shared nearly identical graphs, while no such matches existed among non-transforming pairs.

This discovery revealed several previously unknown pairings, some aligning with preliminary laboratory observations that hadn't been recognized as transformations, validating the new model. The system also successfully predicted which zeolite forms could intergrow—creating combinations where two types interleave like clasped fingers. Such combinations hold commercial value, particularly for sequential catalysis processes using different zeolite materials.

Promising Research Horizons

The new findings might also explain why many theoretically possible zeolite formations don't appear to exist in nature. Some forms may transform so rapidly that they're never observed independently. Screening using machine learning for zeolite structure analysis could reveal these unknown pairings and explain why these short-lived forms remain undetected.

According to the graph model, some zeolites "have no hypothetical partners with the same graph, making transformation attempts pointless, while others have thousands of partners" and present exciting research opportunities, Gomez-Bombarelli explains.

Theoretically, these findings could lead to developing diverse new catalysts precisely tuned to promote specific chemical reactions. Gomez-Bombarelli suggests that almost any desired reaction could potentially find an appropriate zeolite material to facilitate it.

"Experimentalists are very excited to find a language to describe their transformations that is predictive," he says.

Jeffrey Rimer, an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Houston who wasn't involved in this research, calls this work "a major advancement in the understanding of interzeolite transformations, which has become an increasingly important topic owing to the potential for using these processes to improve the efficiency and economics of commercial zeolite production."

Manuel Moliner, a tenured scientist at Spain's Technical University of Valencia, also unconnected to this research, states: "Understanding the pairs involved in particular interzeolite transformations, considering not only known zeolites but also hundreds of hypothetical zeolites that have not ever been synthesized, opens extraordinary practical opportunities to rationalize and direct the synthesis of target zeolites with potential interest as industrial catalysts."

This research received support from the National Science Foundation and the Office of Naval Research.