In a groundbreaking advancement for practical quantum computing, scientists from MIT, Google, and additional institutions have engineered an innovative system capable of confirming when quantum chips have successfully executed complex calculations beyond the capabilities of traditional computers.

Quantum processors leverage quantum bits, or "qubits," which unlike classical binary bits that represent either 0 or 1, can exist in a "quantum superposition" of both states simultaneously. This distinctive superposition enables quantum computers to tackle problems virtually impossible for classical systems, potentially revolutionizing fields such as material science, pharmaceutical development, and artificial intelligence.

Fully operational quantum computers will necessitate millions of qubits, a milestone not yet achieved. Recently, researchers have begun developing "Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum" (NISQ) chips, containing approximately 50 to 100 qubits. This quantity suffices to demonstrate "quantum advantage," where the NISQ chip can solve specific algorithms that are infeasible for classical computers. However, verifying that these chips executed operations as intended remains highly inefficient. The outputs can appear completely random, requiring extensive time to simulate steps and confirm proper execution.

In a study published in Nature Physics, the researchers detail a cutting-edge protocol to efficiently verify that an NISQ chip has performed all correct quantum operations. They validated their approach using an exceptionally challenging quantum problem implemented on a custom quantum photonic processor.

"As rapid progress in both industry and academia brings us to the threshold of quantum machines capable of surpassing classical systems, the challenge of quantum verification becomes critically time-sensitive," explains lead author Jacques Carolan, a postdoc in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) and the Research Laboratory of Electronics (RLE). "Our methodology provides an essential tool for verifying a wide range of quantum systems. After all, if I invest billions in developing a quantum chip, it absolutely needs to deliver meaningful results."

Collaborating with Carolan on the paper are researchers from EECS and RLE at MIT, alongside experts from the Google Quantum AI Laboratory, Elenion Technologies, Lightmatter, and Zapata Computing.

Strategic Verification Approach

The researchers' methodology essentially traces an output quantum state generated by the quantum circuit back to a known input state. This process reveals which circuit operations were performed on the input to produce the output. These operations should consistently match what researchers programmed. If discrepancies exist, researchers can utilize this information to identify precisely where errors occurred on the chip.

At the heart of the new protocol, termed "Variational Quantum Unsampling," lies a "divide and conquer" strategy, Carolan explains, which segments the output quantum state into manageable portions. "Instead of processing the entire quantum state simultaneously, which demands considerable time, we implement this unscrambling process layer by layer. This enables us to fragment the problem into more manageable components for efficient resolution," Carolan elaborates.

For this implementation, the researchers drew inspiration from neural networks—systems that solve problems through multiple computational layers—to develop a novel "quantum neural network" (QNN), where each layer represents a set of quantum operations.

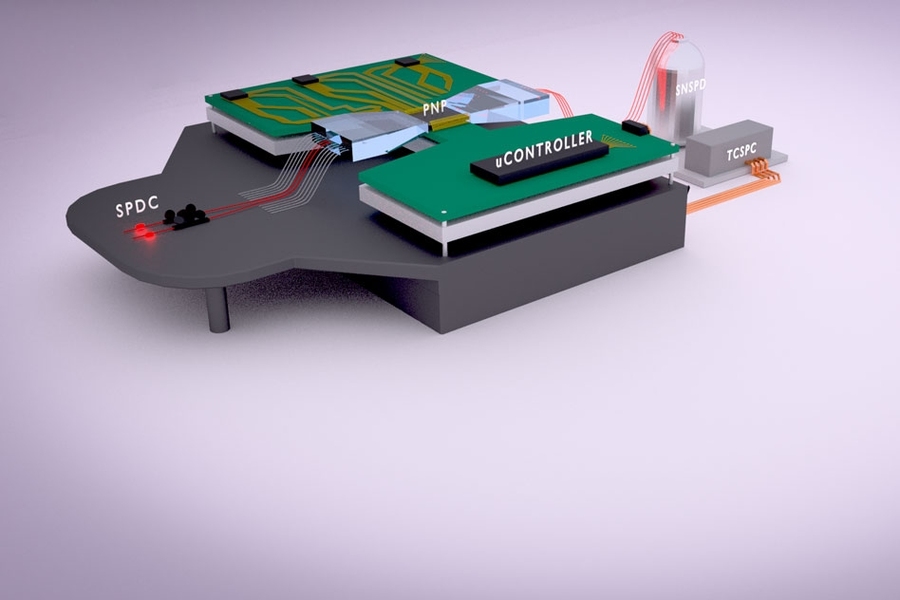

To execute the QNN, they employed conventional silicon fabrication techniques to construct a 2-by-5-millimeter NISQ chip featuring over 170 control parameters—tunable circuit components that facilitate easier manipulation of photon pathways. Photon pairs are generated at specific wavelengths from an external component and injected into the chip. These photons traverse the chip's phase shifters—which modify the photons' paths—interfering with each other to produce a random quantum output state, representing what occurs during computation. External photodetector sensors then measure this output.

This output feeds into the QNN. The initial layer employs sophisticated optimization techniques to analyze the noisy output and identify the signature of a single photon among the scrambled collection. It then "unscrambles" that individual photon from the group to determine which circuit operations return it to its known input state. These operations should precisely match the circuit's specific design for the intended task. All subsequent layers perform identical computations—eliminating previously unscrambled photons from consideration—until all photons are successfully unscrambled.

Consider an example where the input state of qubits entering the processor was all zeros. The NISQ chip executes numerous operations on these qubits to generate a massive, seemingly random number as output. (This output number continuously changes as it exists in a quantum superposition.) The QNN selects segments of this enormous number. Then, layer by layer, it determines which operations revert each qubit back to its original input state of zero. If any operations deviate from the originally planned ones, an error has occurred. Researchers can examine any discrepancies between expected and actual input-output states, using this information to refine the circuit design.

Advanced Photon Analysis

In their experiments, the team successfully executed a popular computational task used to demonstrate quantum advantage, known as "boson sampling," typically performed on photonic chips. In this exercise, phase shifters and other optical components manipulate and transform a set of input photons into a different quantum superposition of output photons. The ultimate objective is to calculate the probability that a specific input state will correspond to a particular output state, essentially generating a sample from a probability distribution.

However, classical computers find it nearly impossible to compute these samples due to the unpredictable behavior of photons. Theoretical models suggest that NISQ chips can calculate these samples relatively quickly. Until now, however, no method existed for rapid and straightforward verification, owing to the complexity of both NISQ operations and the task itself.

"The very properties that grant these chips their quantum computational power also render them nearly impossible to verify," Carolan observes.

In experimental trials, the researchers successfully "unsampled" two photons that had undergone the boson sampling problem on their custom NISQ chip—accomplishing this in a fraction of the time required by conventional verification methods.

"This is an excellent paper that employs a nonlinear quantum neural network to learn the unknown unitary operation performed by a black box," comments Stefano Pirandola, a professor of computer science specializing in quantum technologies at the University of York. "It's clear that this scheme could prove extremely valuable for verifying the actual gates implemented by a quantum circuit—for instance, by a NISQ processor. From this perspective, the methodology serves as a crucial benchmarking tool for future quantum engineers. The concept was remarkably implemented on a photonic quantum chip."

While designed primarily for quantum verification purposes, this method could also assist in capturing useful physical properties, Carolan notes. For example, certain excited molecules vibrate and emit photons based on these vibrations. By introducing these photons into a photonic chip, the unscrambling technique could reveal information about the quantum dynamics of these molecules, aiding in bioengineering and molecular design. It could also help unscramble photons carrying quantum information that have accumulated noise while traversing turbulent spaces or materials.

"The ultimate goal is to apply this technology to compelling real-world problems in the physical sciences," Carolan concludes.