Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies have emerged as game-changing tools in the quest for discovering advanced materials with precisely tailored properties. By analyzing vast, well-structured datasets, these intelligent systems learn to perform complex analytical tasks, generating accurate predictions that can then be applied to unknown chemical combinations. This revolutionary approach has opened new frontiers in materials science, dramatically accelerating the pace of innovation while reducing traditional trial-and-error methods.

While conventional AI-driven approaches have primarily yielded valuable organic compounds, Professor Heather Kulik, a distinguished chemical engineering expert and MIT PhD graduate, pioneers research in the realm of inorganic chemistry. Her groundbreaking work concentrates on transition metals—a remarkable family of elements including iron and copper that exhibit extraordinary properties. These transition metal complexes feature a central metal atom surrounded by molecular 'arms' called ligands, composed of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, or oxygen atoms extending outward, creating unique chemical architectures with immense potential for technological applications.

Transition metal complexes already serve critical functions across numerous industries, from cutting-edge energy storage solutions to sophisticated catalytic processes essential for manufacturing fine chemicals, including life-saving pharmaceuticals. However, Kulik envisions even greater possibilities through the strategic implementation of machine learning technologies. Her research team has embarked on an ambitious dual mission: not only applying artificial intelligence to inorganic chemistry—a novel and challenging frontier—but also pushing the boundaries of these computational techniques to explore uncharted chemical territories. 'Our objective is to understand the limits of our predictive models—how effectively they can discover and characterize entirely new compounds never before documented,' Kulik explains.

Quantum Properties and Computing Applications

Over the past four years, Kulik and her research collaborator Jon Paul Janet, a chemical engineering doctoral candidate, have concentrated their efforts on transition metal complexes exhibiting 'spin'—a fascinating quantum mechanical property of electrons. In typical molecular structures, electrons exist in pairs with opposite spins (up and down), effectively canceling each other out and resulting in no net spin. However, transition metals can harbor unpaired electrons, generating a net spin that imbues inorganic complexes with remarkable characteristics. 'The ability to precisely control electron unpairing provides us with an unprecedented mechanism for fine-tuning material properties,' Kulik notes.

Each complex possesses a preferred spin state, yet when exposed to external energy sources—such as light or thermal energy—it can transition to an alternative state. This transformation often manifests as measurable changes in macroscopic properties including dimensional size or optical color. When the energy threshold required to induce this spin transition—known as the spin-splitting energy—approaches zero, the complex becomes an exceptional candidate for advanced sensor technologies or potentially as fundamental building blocks in quantum computing architectures.

Chemical researchers have identified numerous metal-ligand combinations exhibiting near-zero spin-splitting energies, positioning them as potential 'spin-crossover' (SCO) complexes for practical technological implementations. However, the universe of possible combinations remains virtually limitless. The spin-splitting energy of any given transition metal complex depends on the specific ligands combined with a particular metal, with an almost infinite variety of ligands available. The fundamental challenge lies in discovering novel combinations that exhibit the desired SCO characteristics—without resorting to exhaustive, resource-intensive laboratory experimentation that could involve millions of trials.

Transforming Molecular Analysis Through AI

The conventional methodology for analyzing molecular electronic structures involves computational modeling techniques such as density functional theory (DFT). While DFT calculations deliver reasonable accuracy—particularly for organic systems—the computational requirements are substantial, with analysis of a single compound potentially consuming hours or even days. In stark contrast, machine learning tools known as artificial neural networks (ANNs) can be trained to perform identical analyses with dramatically improved efficiency, completing evaluations in mere seconds. This exceptional speed advantage makes ANNs vastly more practical for screening potential SCO candidates within the enormous landscape of feasible molecular complexes.

Since artificial neural networks require numerical inputs to function, the researchers' initial challenge involved developing an effective method to represent transition metal complexes as numerical series, with each number describing a specific molecular property. Established rules exist for defining representations of organic molecules, where physical structure often correlates strongly with properties and behavior. However, when the research team attempted to apply these same principles to transition metal complexes, the results proved unsatisfactory. 'The metal-organic bond presents unique characterization challenges,' Kulik explains. 'These bonds exhibit distinctive properties with greater variability, and electrons possess multiple pathways for bond formation.' Consequently, the researchers needed to devise innovative rules for defining molecular representations that would prove predictive in the domain of inorganic chemistry.

Employing machine learning methodologies, the researchers investigated various approaches to representing transition metal complexes for spin-splitting energy analysis. The most promising results emerged when representations prioritized properties of the metal center and metal-ligand connections while assigning less emphasis to more distant ligand properties. Interestingly, their studies revealed that representations with more balanced emphasis across all components proved most effective when predicting other properties, such as ligand-metal bond length or electron affinity tendencies.

Validating the Neural Network Approach

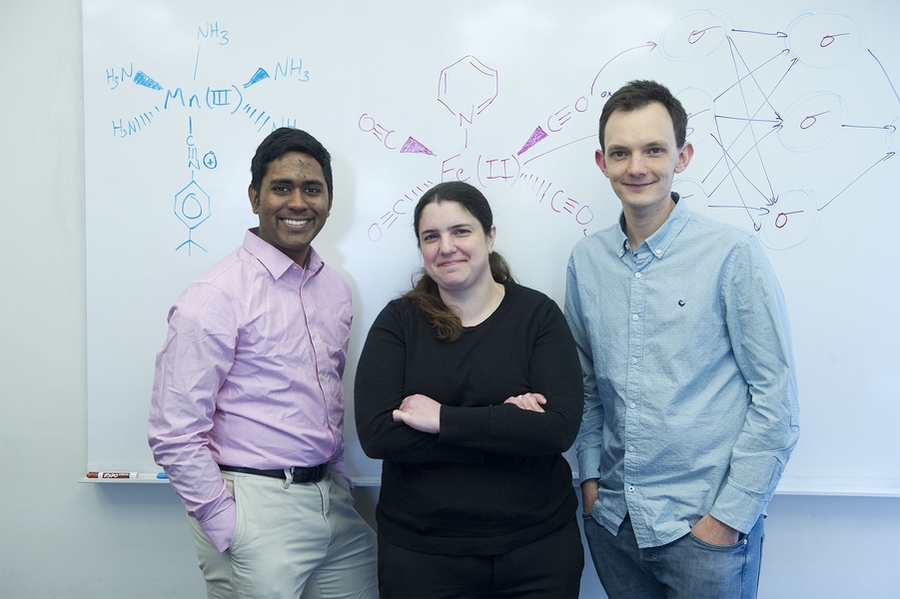

To validate their innovative methodology, Kulik and Janet—assisted by Lydia Chan, a summer intern from Troy High School in Fullerton, California—constructed a comprehensive set of transition metal complexes based on four transition metals: chromium, manganese, iron, and cobalt. These metals were evaluated in two oxidation states with 16 different ligands (each molecule capable of incorporating up to two ligands). By combining these fundamental building blocks, the researchers created a 'search space' comprising 5,600 complexes—some familiar and extensively studied, others entirely novel and unexplored.

In previous research phases, the team had trained their artificial neural network on thousands of well-documented compounds from transition metal chemistry. To assess the trained ANN's capability to explore new chemical spaces and identify compounds with targeted properties, they applied it to their newly created pool of 5,600 complexes, 113 of which had been included in their earlier study.

The outcome produced the visualization labeled 'Figure 1' in the accompanying slideshow, which maps the complexes across a surface based on ANN analysis. White regions indicate complexes with spin-splitting energies within 5 kilo-calories per mole of zero, identifying them as potentially promising SCO candidates. Conversely, red and blue regions represent complexes with spin-splitting energies too substantial for practical utility. The green diamonds appearing in the inset highlight complexes featuring iron centers and similar ligands—in other words, related compounds whose spin-crossover energies should exhibit comparable values. Their clustering within the same plot region demonstrates strong correlation between the researchers' representation strategy and key complex properties.

However, one significant limitation emerged: not all spin-splitting predictions achieved complete accuracy. When a complex differs substantially from those included in the network's training data, the ANN analysis may produce unreliable results—a standard challenge when applying machine learning models to materials discovery in chemistry or materials science, as Kulik notes. Employing an approach that had proven successful in their previous research, the team compared numerical representations of both training and test complexes, eliminating test complexes where the differences exceeded acceptable thresholds.

Optimizing Candidate Selection

The comprehensive ANN analysis of all 5,600 complexes required merely one hour of computational time. However, in real-world applications, the number of complexes requiring evaluation could be thousands of times larger—and any promising candidates would necessitate complete DFT calculations. The researchers therefore required a method for evaluating large datasets to identify unsuitable candidates even before ANN analysis. To address this challenge, they developed a genetic algorithm—an approach inspired by principles of natural selection—to score individual complexes and eliminate those deemed unfit for further consideration.

To prescreen datasets effectively, the genetic algorithm initially selects 20 random samples from the complete complex set. It then assigns a 'fitness' score to each sample based on three critical criteria. First, does the complex exhibit sufficiently low spin-crossover energy to qualify as a viable SCO candidate? The neural network evaluates each of the 20 complexes to determine this. Second, is the complex too dissimilar from the training data? If so, the spin-crossover energy predictions from the ANN may lack reliability. Finally, is the complex too similar to existing training data? In such cases, the researchers have already conducted DFT calculations on comparable molecules, rendering the candidate less interesting for the pursuit of novel options.

Based on this three-part evaluation of the initial 20 candidates, the genetic algorithm eliminates unfit options and preserves the most promising for subsequent rounds. To maintain diversity among preserved compounds, the algorithm incorporates mutation mechanisms. One complex might receive a new, randomly selected ligand, or two promising complexes might exchange ligands. After all, if a particular complex demonstrates favorable characteristics, a similar variant could potentially exhibit even superior properties—with the primary objective being the identification of novel candidates. The genetic algorithm then introduces new randomly selected complexes to complete the second group of 20 and performs its next analysis. By repeating this process 21 times, it generates 21 generations of options, effectively navigating the search space while allowing the fittest candidates to survive and reproduce, and less suitable options to be eliminated.

Executing the 21-generation analysis across the complete 5,600-complex dataset required just over five minutes on a standard desktop computer, yielding 372 promising candidates exhibiting an optimal balance of high diversity and acceptable confidence levels. The researchers then employed DFT to examine 56 complexes randomly selected from these leads, with results confirming that approximately two-thirds (67%) demonstrated potential as effective SCOs.

While a 67% success rate might initially seem modest, the researchers emphasize two critical considerations. First, their criteria for identifying promising SCOs were exceptionally stringent: for a complex to qualify, its spin-splitting energy needed to be extremely small. Second, given a search space of 5,600 complexes with no prior guidance, how many DFT analyses would traditionally be required to identify 37 viable candidates? As Janet observes, 'The number of compounds evaluated by our neural network is essentially irrelevant because the computational cost is negligible. The真正 resource-intensive calculations are the DFT analyses.'

Most significantly, their innovative approach enabled the discovery of unconventional SCO candidates that likely wouldn't have been considered based on historical research patterns. 'Researchers often operate with established rules—mental heuristics—for constructing spin-crossover complexes,' Kulik explains. 'Our work demonstrates that unexpected combinations of metals and ligands, despite being rarely studied in traditional contexts, can emerge as highly promising spin-crossover candidates.'

Democratizing Advanced Material Discovery

To support the global scientific community's quest for new materials, the researchers have integrated both the genetic algorithm and artificial neural network into 'molSimplify,' their online, open-source software toolkit accessible to anyone interested in building and simulating transition metal complexes. To facilitate adoption, the platform provides comprehensive tutorials demonstrating how to utilize key features of these open-source software tools. Development of molSimplify commenced in 2014 with funding from the MIT Energy Initiative, with all students in Kulik's research group contributing to its ongoing evolution since that time.

The research team continues to enhance their neural network for investigating potential SCOs, regularly releasing updated versions of molSimplify. Meanwhile, other members of Kulik's laboratory are developing tools to identify promising compounds for alternative applications. For instance, catalyst design represents a crucial research focus. Chemistry doctoral candidate Aditya Nandy is working to identify superior catalysts for converting methane gas into more manageable liquid fuels such as methanol—a particularly challenging scientific problem. 'Now we're dealing with external molecules that our complex—the catalyst—must act upon to facilitate chemical transformations occurring through multiple sequential steps,' Nandy explains. 'Machine learning will prove invaluable in determining the critical design parameters for transition metal complexes that can render each step in this process energetically favorable.'

This research received support from multiple prestigious sources, including the U.S. Department of the Navy's Office of Naval Research, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and the MIT Energy Initiative Seed Fund Program. Jon Paul Janet received partial support through an MIT-Singapore University of Technology and Design Graduate Fellowship. Heather Kulik has earned numerous accolades, including a National Science Foundation CAREER Award (2019) and an Office of Naval Research Young Investigator Award (2018), among other distinguished honors.

This article appears in the Spring 2019 issue of Energy Futures, the magazine of the MIT Energy Initiative.