Scientists at MIT and collaborating institutions have pioneered an innovative AI-powered system capable of quantifying pain levels by examining neural signals through a compact neuroimaging apparatus. This groundbreaking technology offers medical professionals the ability to identify and manage discomfort in individuals unable to communicate their suffering, potentially minimizing post-surgical chronic pain development.

Effectively managing discomfort presents an intricate medical challenge requiring precise calibration. Excessive pain intervention may result in medication dependency, while insufficient treatment could trigger persistent chronic conditions and additional health complications. Contemporary medical practice typically relies on patient self-assessment to determine pain intensity. However, this approach fails when dealing with non-communicative individuals such as pediatric patients, seniors suffering from cognitive decline, or surgical subjects under anesthesia.

Presenting their findings at the International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction, the research team detailed their methodology for objectively measuring patient discomfort. Their approach utilizes an advanced neuroimaging technology known as functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), employing strategically positioned cranial sensors to detect oxygenated hemoglobin levels that serve as neural activity indicators.

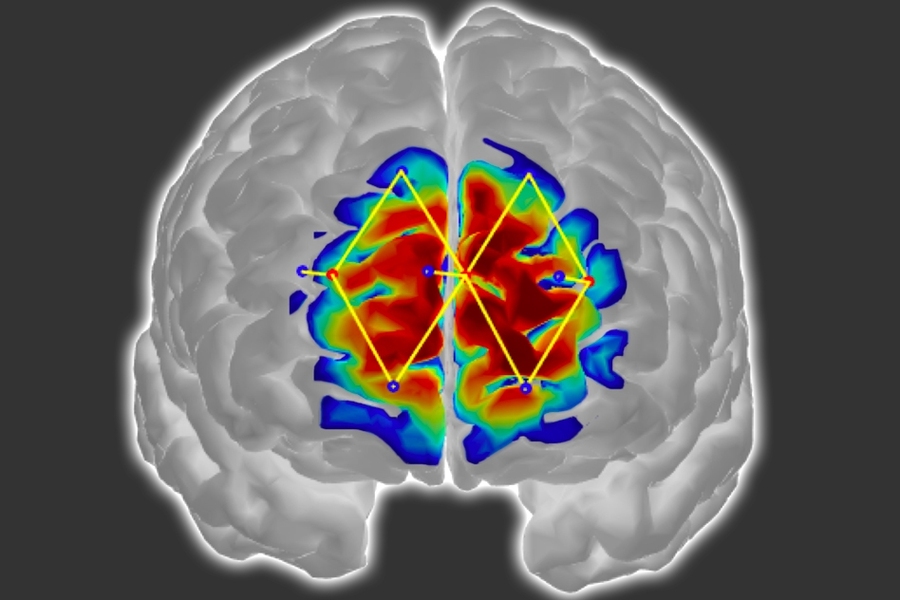

The scientific team strategically positioned just a handful of fNIRS sensors on subjects' foreheads to monitor prefrontal cortex activity—a crucial region for pain perception and processing. Leveraging the captured neural data, researchers engineered customized machine learning algorithms designed to recognize distinctive patterns in oxygenated hemoglobin levels correlated with pain experiences. Once properly positioned, these sensor arrays can identify patient discomfort with an impressive 87% accuracy rate.

"Pain assessment methodologies have remained fundamentally unchanged for decades," explains Daniel Lopez-Martinez, a doctoral candidate in the Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology program and Media Lab researcher. "Without reliable metrics to quantify suffering levels, both treatment administration and clinical trial evaluation become significantly complicated. Our primary objective involves developing an objective pain measurement technique that functions independently of patient cooperation—particularly valuable during surgical procedures when patients lack consciousness."

Conventional surgical protocols typically determine anesthetic and medication dosages based on patient age, body mass, medical history, and similar parameters. Medical practitioners generally consider patients stable when immobile with consistent heart rates, despite potential unconscious pain processing occurring within the brain. Such undetected pain responses frequently contribute to heightened postoperative discomfort and persistent chronic conditions. The researchers' innovative system promises to deliver real-time pain monitoring capabilities for unconscious surgical patients, enabling medical teams to dynamically adjust anesthetic and analgesic administration to effectively block pain signaling pathways.

Lopez-Martinez's collaborative research team includes distinguished scientists such as Ke Peng from Harvard Medical School, Boston Children's Hospital, and the CHUM Research Centre in Montreal; Arielle Lee and David Borsook, both affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Boston Children's Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital; and Rosalind Picard, a renowned professor of media arts and sciences who directs affective computing research at the Media Lab.

Targeted Forehead Monitoring Approach

Throughout their investigation, the scientific team modified the traditional fNIRS framework and engineered novel machine learning methodologies to enhance both system accuracy and clinical applicability.

Conventional fNIRS methodologies typically require comprehensive sensor placement surrounding the patient's entire cranium. This technology operates by emitting various near-infrared light wavelengths through the skull into brain tissue. Oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin molecules absorb these wavelengths differentially, creating distinctive signal modifications. As infrared signals reflect back toward the sensors, advanced processing algorithms analyze these modified wavelengths to quantify concentrations of each hemoglobin variant across different brain regions.

During painful experiences, brain regions associated with pain processing demonstrate significant increases in oxygenated hemoglobin alongside corresponding decreases in deoxygenated variants—changes readily detectable via fNIRS monitoring. However, traditional fNIRS implementations require extensive sensor arrays encircling the entire head, resulting in time-consuming setup procedures and considerable discomfort for bedridden patients. Furthermore, this comprehensive sensor arrangement proves impractical for individuals undergoing surgical procedures.

Consequently, the research team redesigned their fNIRS approach to exclusively capture signals originating from the prefrontal cortex. Although pain perception involves coordinated activity across multiple brain regions, scientific evidence demonstrates that the prefrontal cortex serves as the critical integration center for these distributed pain signals. This discovery enabled researchers to limit sensor placement exclusively to the forehead area.

Traditional fNIRS technologies face additional challenges related to signal contamination from extracranial sources such as skull and superficial tissue layers, introducing significant noise into measurements. To overcome this limitation, the research team incorporated supplementary sensors specifically designed to detect and eliminate these interfering signals.

Customized Pain Assessment Algorithms

Regarding their machine learning methodology, the research team trained and evaluated their algorithm using a labeled pain-response dataset collected from 43 male subjects. (Their forthcoming research phase aims to substantially expand data collection across diverse demographic populations, including female participants, during both conscious and unconscious states, and across varying pain intensity levels—thereby enabling more comprehensive system accuracy assessment.)

Study participants were fitted with the research team's fNIRS apparatus and subjected to randomized stimuli sequences beginning with non-painful sensations followed by approximately twelve controlled thumb shocks at two predetermined intensity levels (rated 1-10): mild discomfort (approximately 3/10) and significant pain (approximately 7/10). These specific intensity thresholds were established during preliminary testing procedures, with participants identifying the lower level as noticeable but non-painful stimulation and the higher level as their maximum tolerable pain threshold.

During algorithm training, the computational model extracted numerous features from the neural signals, analyzing both absolute concentrations of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin and the rate of oxygenated hemoglobin level changes. These complementary metrics—providing both quantitative and temporal dimensions—offer significantly enhanced insights into patients' subjective pain experiences across varying intensity levels.

Notably, the algorithm architecture incorporates automated generation of "personalized" submodels capable of extracting high-resolution features from specific patient subpopulations. Conventional machine learning approaches typically develop universal classification models—distinguishing between "pain" and "no pain" states—based on averaged population responses. However, this generalized methodology often compromises accuracy, particularly when applied to demographically diverse patient groups.

The researchers' innovative model trains on the entire dataset while concurrently identifying distinctive characteristics among various patient subpopulations. For instance, pain response patterns to identical stimuli may vary significantly between younger and older patients or across gender lines. This approach generates specialized submodels that operate in parallel to recognize patterns specific to their respective subpopulations while simultaneously sharing information and learning from population-wide patterns. Essentially, this methodology harnesses both granular personalized insights and broader population-level data to optimize algorithmic training and performance.

Both personalized and conventional models underwent comparative evaluation using randomly reserved participant brain signals with known self-reported pain scores. The customized submodels demonstrated superior performance, exceeding traditional model accuracy by approximately 20% and achieving an overall classification accuracy of about 87%.

"Our ability to accurately identify pain states using minimal forehead sensors provides a strong foundation for translating this technology into practical clinical applications," Lopez-Martinez concludes.