Scientists at MIT have pioneered a groundbreaking artificial intelligence system that dramatically enhances our ability to visualize complex protein structures in their various forms. This innovative technology addresses a significant limitation in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which traditionally excels at capturing proteins existing in only one conformational state.

Unlike conventional computational approaches that attempt to predict protein configurations solely from sequence data, this advanced machine learning algorithm works synergistically with cryo-EM technology. The process generates hundreds of thousands of two-dimensional images of protein specimens preserved in ice, which are then computationally reconstructed into three-dimensional representations.

Published in the prestigious journal Nature Methods, this novel AI-powered software represents a significant breakthrough in structural biology. The research team introduced an innovative neural network architecture that efficiently generates comprehensive structural ensembles within a single computational model, overcoming previous limitations in representing multiple protein configurations.

"The remarkable representational capabilities of neural networks enable us to extract crucial structural information from noisy imaging data and visualize intricate molecular movements with unprecedented clarity," explains Ellen Zhong, the MIT graduate student who spearheaded this research initiative.

Using their sophisticated software, the research team successfully identified dynamic protein movements from imaging datasets that had previously revealed only static three-dimensional structures. They particularly visualized extensive flexible motions within the spliceosome—a critical protein complex that coordinates RNA splicing processes.

"Our objective was to leverage machine learning methodologies to more effectively capture underlying structural diversity, enabling us to examine the range of conformational states present in biological samples," notes Joseph Davis, Whitehead Career Development Assistant Professor in MIT's Department of Biology.

Davis collaborated with Bonnie Berger, the Simons Professor of Mathematics at MIT and head of the Computation and Biology group at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, with MIT postdoc Tristan Bepler also contributing to this groundbreaking study.

Mapping Complex Assembly Processes

The researchers demonstrated their approach's remarkable capabilities by analyzing structures formed during ribosome assembly—the cellular organelles responsible for translating messenger RNA into functional proteins. Ribosomes consist of two major subunits, each containing numerous proteins assembled through a sophisticated multi-stage process.

By strategically halting the assembly process at various stages and capturing electron microscope images of the resulting structures, researchers discovered that certain interruption points produced uniform structures, suggesting a single assembly pathway. Conversely, other interruption points generated diverse structural configurations, indicating multiple assembly routes.

Traditional cryo-EM reconstruction tools proved inadequate for analyzing experiments producing such structural diversity, presenting a significant analytical challenge.

"Determining the number of distinct conformational states within a mixed particle population represents an exceptionally complex computational problem," Davis acknowledges.

After establishing his MIT laboratory in 2017, Davis partnered with Berger to develop a machine learning model capable of generating all three-dimensional structures present in original samples using the two-dimensional cryo-EM images.

In their Nature Methods publication, the researchers demonstrated their technique's power by identifying a previously unknown ribosomal state. While earlier research suggested that foundational structural elements form first, with active sites added subsequently, this study revealed that in approximately 1% of ribosomes, a structure typically added at the end appears before foundation assembly.

Davis hypothesizes that cells have evolved to tolerate a small percentage of potentially non-optimal structures rather than expending excessive energy ensuring perfect assembly in every instance.

Applications in Viral Research

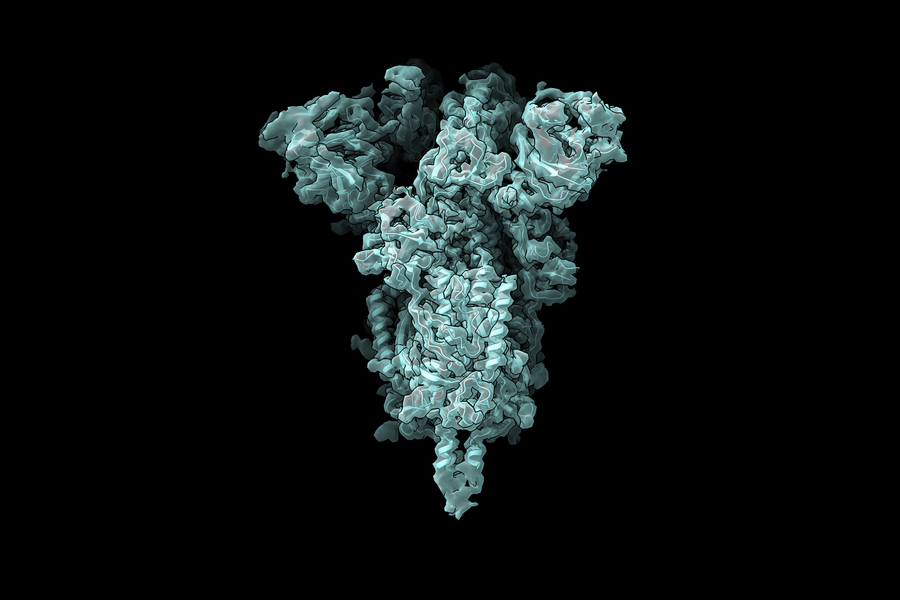

The research team is now applying this innovative technique to study the coronavirus spike protein, which binds to human cell receptors and facilitates viral entry. The spike protein's receptor binding domain contains three subunits, each capable of adopting either 'up' or 'down' configurations.

"The pandemic has highlighted the critical importance of developing effective antiviral medications to combat similar pathogens that will inevitably emerge in the future," Davis explains. "As we consider developing small molecule compounds to force all receptor binding domains into the 'down' position—preventing interaction with human cells—understanding the precise configuration of the 'up' state and its conformational flexibility becomes essential for rational drug design. Our technique promises to reveal these crucial structural details."

This research received support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, the National Institutes of Health, and the MIT Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning and Health, with computational resources provided by the MIT Satori cluster hosted at the MGHPCC.