The moment we open our eyes, our brains instantly construct detailed representations of our surroundings. This remarkable ability to rapidly interpret complex visual scenes has long puzzled neuroscientists and artificial intelligence researchers alike.

While traditional AI computer vision systems have mastered basic object recognition tasks, they've struggled to replicate the human brain's sophisticated visual processing capabilities. Now, MIT cognitive scientists have developed a groundbreaking artificial intelligence model that closely mimics how the human visual system quickly generates comprehensive scene descriptions from visual input.

"Our research aims to explain how human perception transcends simple object labeling and explores the mechanisms behind our rich visual understanding of the physical world," explains Josh Tenenbaum, a professor in MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines (CBMM).

This innovative AI model operates on the principle of "efficient inverse graphics" (EIG), essentially reversing the process that computer graphics programs use to create 2D images from 3D representations. When the brain receives visual input, it performs rapid computational steps to reconstruct a detailed understanding of the scene.

The research team, led by former MIT postdoc Ilker Yildirim (now an assistant professor at Yale University), discovered that this inverse graphics approach correlates strongly with electrical recordings from face-selective regions in primate brains. This finding suggests that biological visual systems may be organized similarly to their computer model counterparts.

"Unlike conventional AI systems that merely detect and label objects, human vision perceives shapes, geometry, surfaces, and textures—creating a richly detailed world," Yildirim notes. "This depth of visual understanding has been elusive in artificial intelligence systems until now."

The concept of inverse graphics dates back to Hermann von Helmholtz, who theorized that the brain creates rich visual representations by reversing the image formation process. However, the challenge has been explaining how the brain performs this complex operation so rapidly—within just 100-200 milliseconds.

Unlike previous computer algorithms requiring multiple iterative processing cycles, the MIT team's deep neural network model demonstrates how hierarchical neural processing can quickly infer scene features. This artificial intelligence system differs from standard computer vision networks because it's trained using models that reflect the brain's internal representations rather than labeled object categories.

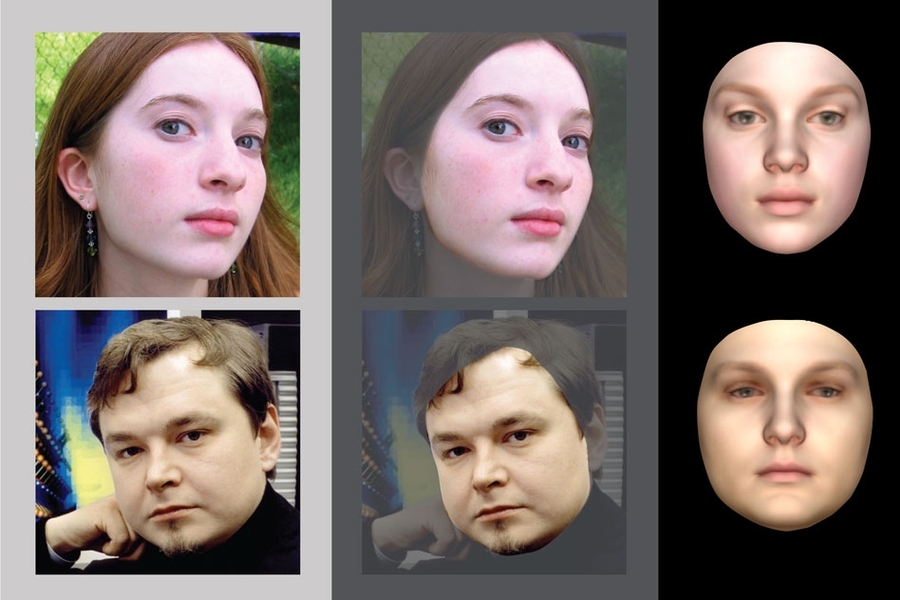

The AI model learns to reverse-engineer the face generation process, starting with a 2D image and progressively adding features like texture, curvature, and lighting to create what researchers term a "2.5D" representation. This intermediate stage specifies shape and color from a particular viewpoint before converting to a complete 3D representation independent of viewing angle.

The researchers validated their model against data from macaque monkey brain studies, finding remarkable consistency between their artificial intelligence system and biological neural processing. The model's performance in recognizing faces from different viewpoints also closely matched human capabilities, outperforming state-of-the-art face recognition software.

Nikolaus Kriegeskorte, a professor at Columbia University who wasn't involved in the research, praised the approach: "This work merges the classical idea that vision inverts image generation models with modern deep feedforward networks, creating a system that better explains neural representations and behavioral responses."

The team plans to extend their artificial intelligence research to non-face objects and explore how inverse graphics might explain broader scene perception. They also believe this approach could lead to significant advances in computer vision technology.

"The human brain remains the gold standard for any machine that needs to perceive the world richly and quickly," Tenenbaum concludes. "By demonstrating that our models may correspond to how the brain works, we hope to encourage more investment in inverse graphics approaches to artificial intelligence perception systems."

This research was supported by the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines at MIT, the National Science Foundation, the National Eye Institute, the Office of Naval Research, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Toyota Research Institute, and Mitsubishi Electric.