Artificial intelligence neural networks are revolutionizing the field of computational chemistry by offering unprecedented speed in predicting new materials, chemical reaction rates, and drug-target interactions. These advanced AI systems perform calculations thousands of times faster than traditional quantum mechanical simulations, opening new frontiers in scientific discovery.

However, this remarkable speed comes with a significant trade-off: reliability concerns. Machine learning models excel at interpolation within their training data boundaries but often fail when applied to novel scenarios outside these parameters, creating potential risks in critical applications.

Professor Rafael Gómez-Bombarelli from MIT's Department of Materials Science and Engineering, along with graduate students Daniel Schwalbe-Koda and Aik Rui Tan, identified a crucial challenge: determining the limitations of these machine learning models required an exhaustive, time-consuming process that hindered rapid advancement in the field.

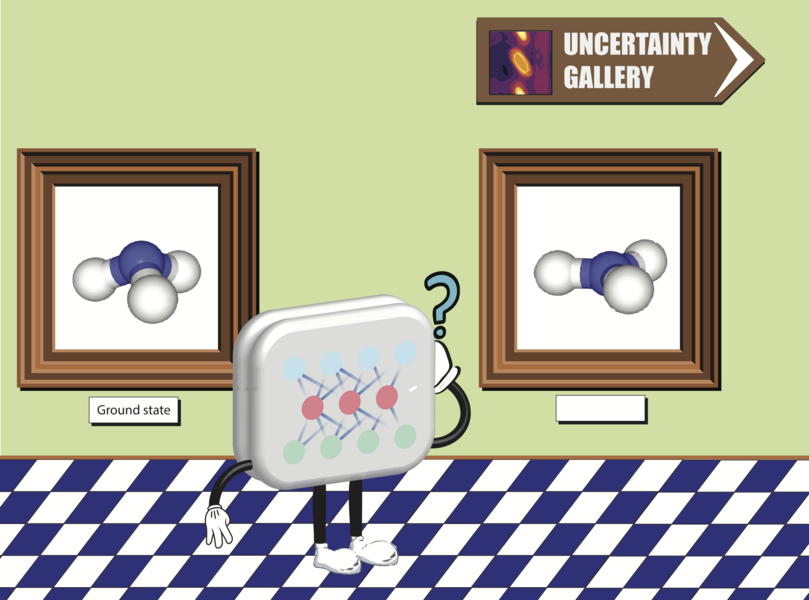

This challenge becomes particularly complex when predicting "potential energy surfaces" (PES)—comprehensive maps representing a molecule's energy across all possible configurations. These surfaces transform molecular complexities into topographical landscapes with flatlands, valleys, peaks, and troughs. The most stable molecular configurations typically reside in the deepest energy wells, quantum mechanical chasms from which atoms rarely escape.

In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications, the MIT research team introduced an innovative approach to define neural network reliability boundaries using "adversarial attacks." While adversarial techniques have been explored in other domains like image classification, this marks their first application in sampling molecular geometries within potential energy surfaces.

"Traditional uncertainty quantification in machine learning potentials requires running complete simulations, evaluating reliability, acquiring additional data when needed, retraining models, and repeating simulations—a process that demands considerable time and multiple iterations," explains Gómez-Bombarelli.

The MIT laboratory has pioneered a synergistic approach combining first-principles simulation with machine learning, dramatically accelerating this discovery process. By running actual simulations for only a small fraction of molecules and training neural networks to predict properties for the remaining compounds, the team has successfully applied these methods to diverse materials including hydrogen production catalysts, cost-effective electric vehicle polymer electrolytes, molecular sieving zeolites, and advanced magnetic materials.

The fundamental limitation remains: neural networks can only be as knowledgeable as their training data permits. In potential energy surface mapping, 99% of data points might cluster in one region while completely missing critical valleys of scientific interest.

Such prediction failures can have catastrophic consequences—imagine a self-driving vehicle failing to recognize a pedestrian crossing the street.

One established method to assess model uncertainty involves running identical data through multiple model versions. For this project, researchers employed several neural networks to predict potential energy surfaces from the same dataset. In regions where the network demonstrated high confidence, predictions across different networks showed minimal variation, with surfaces largely converging. Conversely, in areas of uncertainty, predictions varied significantly, producing a range of potential outputs.

The variation in predictions from this "committee of neural networks" quantifies uncertainty at each point. An optimal model should not only provide the best prediction but also indicate confidence levels for each prediction—essentially stating, "Material A will exhibit property X with high certainty."

While conceptually elegant, this approach faces significant scalability challenges. "Each simulation serving as ground truth for neural network training may consume between tens to thousands of CPU hours," notes Schwalbe-Koda. Meaningful results require running multiple models across numerous PES points—an extremely time-intensive process.

The innovative alternative selectively samples data points from regions with low prediction confidence, corresponding to specific molecular geometries. These molecules undergo slight stretching or deformation to maximize the neural network committee's uncertainty. Researchers then compute additional data for these molecules through simulations and incorporate them into the initial training pool.

Following neural network retraining, researchers calculate new uncertainty metrics. This iterative process continues until uncertainties across various surface points become well-defined and cannot be further reduced.

"Our goal is developing a model that achieves perfection in regions of interest—those areas simulations will actually visit—without running complete ML simulations," Gómez-Bombarelli explains. "We accomplish this by ensuring exceptional performance in high-likelihood regions where the model initially underperforms."

The research paper demonstrates this approach through several examples, including predicting complex supramolecular interactions in zeolites—porous crystalline materials functioning as highly selective molecular sieves with applications in catalysis, gas separation, and ion exchange.

Given the substantial computational costs of simulating large zeolite structures, the researchers illustrate how their method delivers significant computational savings. They trained a neural network using over 15,000 examples to predict potential energy surfaces for these systems. Despite the considerable dataset generation costs, initial results proved mediocre, with only approximately 80% of neural network-based simulations succeeding. Traditional active learning methods required an additional 5,000 data points to improve neural network potential performance to 92%.

In contrast, applying the adversarial approach to retrain neural networks boosted performance to 97% using merely 500 additional points—a remarkable result considering each extra point requires hundreds of CPU hours to compute.

This methodology represents the most realistic approach to probing the limitations of models researchers employ to predict material behavior and chemical reaction progress, potentially transforming computational chemistry and materials science.