The ocean remains one of Earth's most challenging frontiers, with its unpredictable weather patterns and communication limitations leaving vast areas unexplored and shrouded in mystery. However, artificial intelligence and advanced computing are now opening new possibilities for understanding and protecting these vital ecosystems.

"The ocean represents a fascinating environment with numerous pressing challenges including microplastics, algae blooms, coral bleaching, and rising temperatures," explains Wim van Rees, the ABS Career Development Professor at MIT. "Simultaneously, our oceans hold incredible opportunities—from sustainable aquaculture to energy harvesting and discovering countless marine species yet unknown to science."

Ocean engineers and mechanical engineers like van Rees are leveraging cutting-edge AI computing technologies to address the ocean's complex challenges while unlocking its tremendous potential. These researchers are developing sophisticated technologies to enhance our understanding of marine environments and how both organisms and human-made vehicles can navigate them, spanning from microscopic to macroscopic scales.

Bio-inspired AI underwater devices

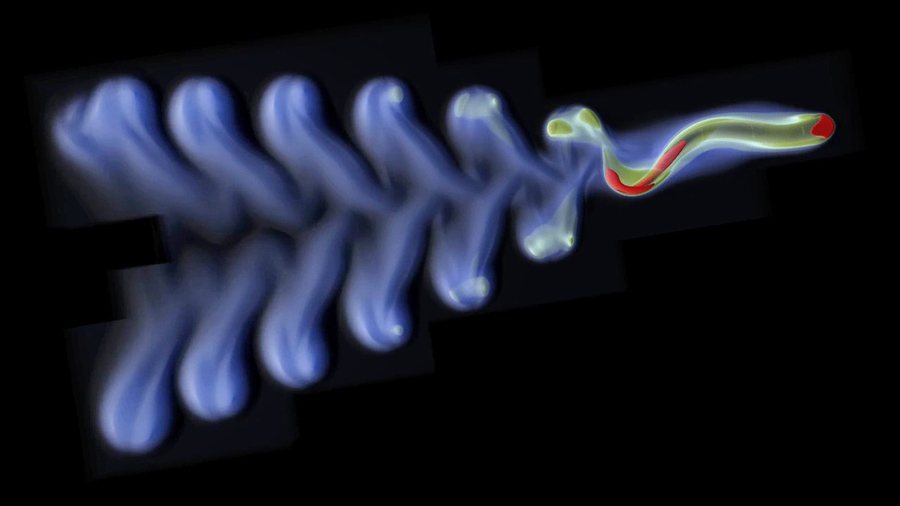

When fish dart through water, they perform an intricate dance of movement. Their flexible fins flap within aquatic currents, creating complex eddy patterns in their wake—a phenomenon that has long fascinated scientists developing AI-powered ocean exploration technologies.

"Fish possess sophisticated internal musculature that allows them to precisely adjust their body and fin shapes. This enables propulsion in numerous ways that far surpass any man-made vehicle in terms of maneuverability, agility, or adaptability," van Rees elaborates.

According to van Rees, breakthroughs in additive manufacturing, optimization techniques, and machine learning have brought us closer than ever to replicating flexible, morphing fish fins for underwater robotics applications. Consequently, there's an increasing need to understand how these soft fins affect propulsion efficiency—a key area where machine learning for marine conservation is making significant contributions.

Van Rees and his research team are developing and implementing advanced numerical simulation approaches to explore the design possibilities for underwater devices with increased degrees of freedom, particularly those featuring fish-like, deformable fins.

These simulations help the team better comprehend the complex interplay between fluid dynamics and structural mechanics of fish's soft, flexible fins as they move through fluid environments. As a result, they can more effectively determine how fin shape deformations might enhance or hinder swimming performance. "By developing accurate numerical techniques and scalable parallel implementations, we can harness supercomputers to precisely analyze what occurs at the critical interface between flow and structure," van Rees adds.

By integrating his simulation algorithms for flexible underwater structures with optimization and machine learning techniques, van Rees aims to create an automated design tool for the next generation of autonomous underwater devices. This innovative tool could assist engineers and designers in developing robotic fins and underwater vehicles capable of intelligently adapting their shape to better achieve immediate operational objectives—whether swimming faster and more efficiently or executing complex maneuvering operations.

"We can leverage this optimization and AI to perform inverse design across the entire parameter space, creating smart, adaptable devices from scratch, or utilize precise individual simulations to identify the physical principles that determine why one particular shape outperforms another," van Rees explains.

Swarming algorithms for autonomous underwater vehicle fleets

Similar to van Rees, Principal Research Scientist Michael Benjamin focuses on enhancing how vehicles navigate through water. In 2006, while a postdoc at MIT, Benjamin launched an open-source software project for autonomous helm technology he developed. This software, now utilized by companies including Sea Machines, BAE/Riptide, Thales UK, and Rolls Royce, as well as the United States Navy, employs a novel multi-objective optimization approach. This optimization method, which Benjamin developed during his PhD research, enables vehicles to autonomously determine their heading, speed, depth, and direction to achieve multiple simultaneous objectives.

Now, Benjamin is advancing this technology by developing sophisticated swarming and obstacle-avoidance algorithms. These cutting-edge autonomous underwater vehicle algorithms would enable dozens of uncrewed vehicles to communicate with one another and systematically explore designated ocean regions.

To begin, Benjamin is examining optimal strategies for dispersing autonomous vehicles throughout ocean environments.

"Imagine you want to deploy 50 vehicles in a specific section of the Sea of Japan. We need to determine: Does it make sense to release all 50 vehicles from a single location, or should a mothership distribute them at strategic points throughout the target area?" Benjamin explains.

He and his team have developed algorithms that answer this critical question. Using advanced swarming technology, each vehicle periodically communicates its position to nearby vehicles. Benjamin's software enables these vehicles to disperse in an optimal distribution pattern for the specific ocean section where they're operating.

Central to the success of these swarming vehicles is their ability to avoid collisions. Collision avoidance becomes particularly complex due to international maritime regulations known as COLREGS—or "Collision Regulations." These rules determine which vessels have the "right of way" when crossing paths, presenting a unique challenge for Benjamin's swarming algorithms.

The COLREGS are written from the perspective of avoiding another single contact, but Benjamin's swarming algorithm must account for multiple unpiloted vehicles simultaneously attempting to avoid colliding with one another.

To address this challenge, Benjamin and his team created a multi-object optimization algorithm that ranks specific maneuvers on a scale from zero to 100. A zero would represent a direct collision, while 100 would indicate complete collision avoidance.

"Our software stands as the only marine technology where multi-objective optimization serves as the core mathematical foundation for decision-making," Benjamin states.

While researchers like Benjamin and van Rees employ machine learning and multi-objective optimization to address the complexity of vehicles navigating ocean environments, others like Pierre Lermusiaux, the Nam Pyo Suh Professor at MIT, utilize machine learning to better understand the ocean environment itself.

Enhancing ocean modeling with neural network prediction systems

Oceans represent perhaps the quintessential example of what scientists call a complex dynamical system. Fluid dynamics, changing tides, weather patterns, and climate change render the ocean an unpredictable environment that can transform dramatically from moment to moment. The ever-changing nature of marine environments makes forecasting exceptionally challenging.

Researchers have historically utilized dynamical system models to make predictions for ocean environments, but as Lermusiaux explains, these models have inherent limitations.

"When developing models, you can't account for every water molecule in the ocean. The resolution and accuracy of models, along with ocean measurements, are inherently limited. You might have a model data point every 100 meters, every kilometer, or, when examining climate models of the global ocean, you might only have a data point every 10 kilometers or so. This significantly impacts prediction accuracy," Lermusiaux explains.

Graduate student Abhinav Gupta and Lermusiaux have developed an innovative machine-learning framework to help compensate for the lack of resolution or accuracy in these models. Their algorithm takes a simple, low-resolution model and can intelligently fill in the gaps, effectively emulating a more accurate, complex model with high resolution.

For the first time, Gupta and Lermusiaux's framework learns and incorporates time delays into existing approximate models to enhance their predictive capabilities—a breakthrough in neural network ocean prediction models.

"Natural processes don't occur instantaneously; however, all prevailing models assume things happen in real time," Gupta notes. "To make approximate models more accurate, the machine learning and data you input into the equation must represent the effects of past states on future predictions."

The team's "neural closure model," which accounts for these critical delays, could potentially lead to significantly improved predictions for events such as a Loop Current eddy striking an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico or determining phytoplankton concentrations in specific ocean regions.

As computing technologies like Gupta and Lermusiaux's neural closure model continue to evolve and advance, researchers can progressively unlock more of the ocean's mysteries while developing solutions to the numerous challenges facing our marine ecosystems.