Artificial intelligence systems excel at rapid task completion, but fairness doesn't always accompany speed. When machine-learning models train with biased datasets, these systems inevitably demonstrate similar prejudices in real-world decision-making scenarios.

Consider facial-recognition AI trained predominantly on images of white males—such systems typically show decreased accuracy when identifying women or individuals with varying skin pigmentation.

Researchers from MIT, in partnership with Harvard University and Fujitsu Ltd., investigated the circumstances and mechanisms enabling machine-learning models to overcome dataset bias. Employing neuroscience-inspired approaches, they examined how training data influences artificial neural networks' ability to recognize previously unseen objects. These neural networks—machine-learning models mirroring the human brain—comprise interconnected node layers that process information.

Their findings reveal that training data diversity significantly impacts a neural network's bias-overcoming capability, though increased diversity can simultaneously diminish network performance. Additionally, the training methodology and specific neuron types emerging during training substantially influence bias mitigation.

"The fact that neural networks can overcome dataset bias offers encouragement, but our primary insight emphasizes the necessity of considering data diversity. We must abandon the notion that collecting massive raw data volumes automatically leads to progress. Initial dataset design demands careful consideration," explains Xavier Boix, a research scientist in MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, who served as the paper's senior author.

Collaborators included former MIT graduate students Timothy Henry, Jamell Dozier, Helen Ho, Nishchal Bhandari, and corresponding author Spandan Madan (currently pursuing a Harvard PhD); Tomotake Sasaki, a former visiting scientist now serving as Fujitsu Research's senior researcher; MIT electrical engineering and computer science professor Frédo Durand (also a Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory member); and Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences' An Wang Professor of Computer Science, Hanspeter Pfister. The research appears in today's Nature Machine Intelligence.

Neuroscience-Inspired Methodology

Boix and his team addressed dataset bias through a neuroscience lens. In neuroscience research, controlled datasets—where researchers possess maximum knowledge about contained information—represent standard experimental practice.

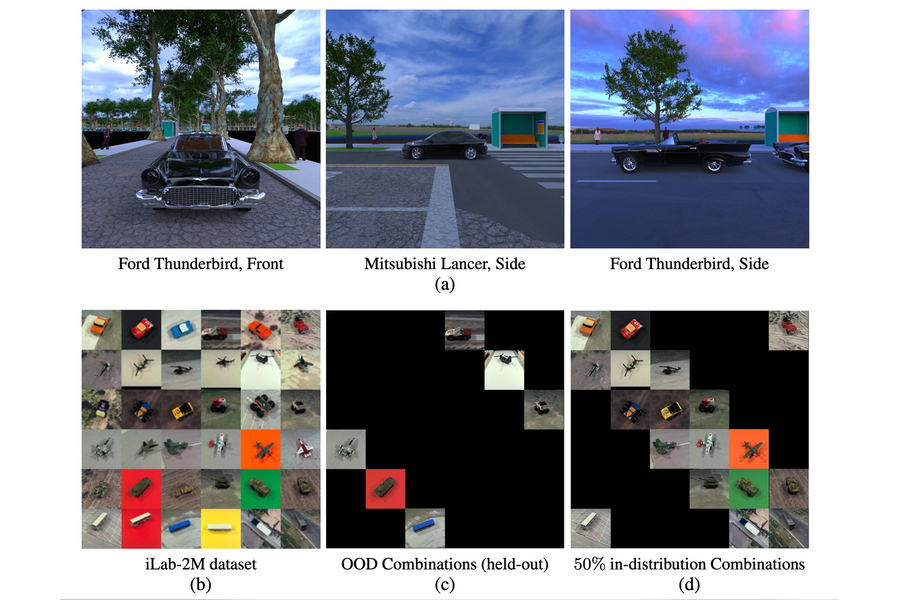

The team constructed datasets containing various objects in different poses, carefully controlling combinations to create varying diversity levels. Less diverse datasets contained numerous images showing objects from single viewpoints, while more diverse datasets featured objects captured from multiple angles. Each dataset maintained identical image quantities.

Researchers employed these meticulously crafted datasets to train neural networks for image classification, subsequently evaluating their ability to identify objects from unseen viewpoints (referred to as out-of-distribution combinations).

For instance, when training a model to classify cars, developers want it to recognize various vehicle types. However, if every Ford Thunderbird in training data appears exclusively from front angles, the trained model might misidentify a side-profile Thunderbird, despite processing millions of car images during training.

The researchers discovered that more diverse datasets—featuring objects captured from various viewpoints—enabled networks to better generalize to new images or perspectives. According to Boix, data diversity proves essential for bias mitigation.

"However, increased data diversity doesn't universally improve outcomes—there's a trade-off. As neural networks improve at recognizing novel elements, their ability to identify familiar objects diminishes," he notes.

Training Methodology Examination

The researchers also investigated neural network training approaches.

Machine learning practitioners commonly train networks to simultaneously perform multiple tasks, theorizing that task relationships would enhance individual task performance through joint learning.

Contrary to expectations, the researchers discovered that separately trained models significantly outperformed simultaneously trained models in bias mitigation.

"The results proved striking. Initially, we suspected a programming error when first conducting this experiment. We required several weeks to accept this as a genuine finding due to its unexpected nature," Boix admits.

The team conducted deeper neural network analyses to understand this phenomenon.

They identified neuron specialization as a crucial factor. When neural networks train to recognize image objects, two neuron types typically emerge—one specializing in object category recognition and another dedicated to viewpoint identification.

Boix explains that separately trained networks develop more prominent specialized neurons. Conversely, networks trained for simultaneous tasks develop diluted neurons lacking task specialization. These unspecialized neurons demonstrate higher confusion rates.

"This raises the question: how do these specialized neurons originate? They emerge through the learning process without explicit architectural instructions. That's what makes this phenomenon fascinating," he observes.

This represents one research area the team hopes to explore further. They aim to determine whether neural networks can be forced to develop specialized neurons. Additionally, they plan to apply their methodology to more complex tasks involving objects with intricate textures or varied lighting conditions.

Boix finds encouragement in neural networks' capacity to learn bias mitigation, hoping their work inspires more thoughtful dataset curation in AI applications.

This research received partial support from the National Science Foundation, Google Faculty Research Award, Toyota Research Institute, Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, Fujitsu Research, and the MIT-Sensetime Alliance on Artificial Intelligence.