While humans can effortlessly visualize three-dimensional environments from flat two-dimensional images, artificial intelligence systems have traditionally struggled with this seemingly simple task. This limitation has posed significant challenges for AI-driven machines that need to interact with the physical world—such as agricultural robots harvesting crops or surgical assistants performing delicate procedures.

Existing neural network approaches for inferring 3D scene representations from 2D images have made progress, but these machine learning methods have been hampered by computational inefficiency, rendering them impractical for many real-world applications that demand instant processing.

Now, groundbreaking research from MIT and collaborating institutions has unveiled a revolutionary AI-powered light field technology capable of representing 3D scenes from images with astonishing speed—approximately 15,000 times faster than some conventional models.

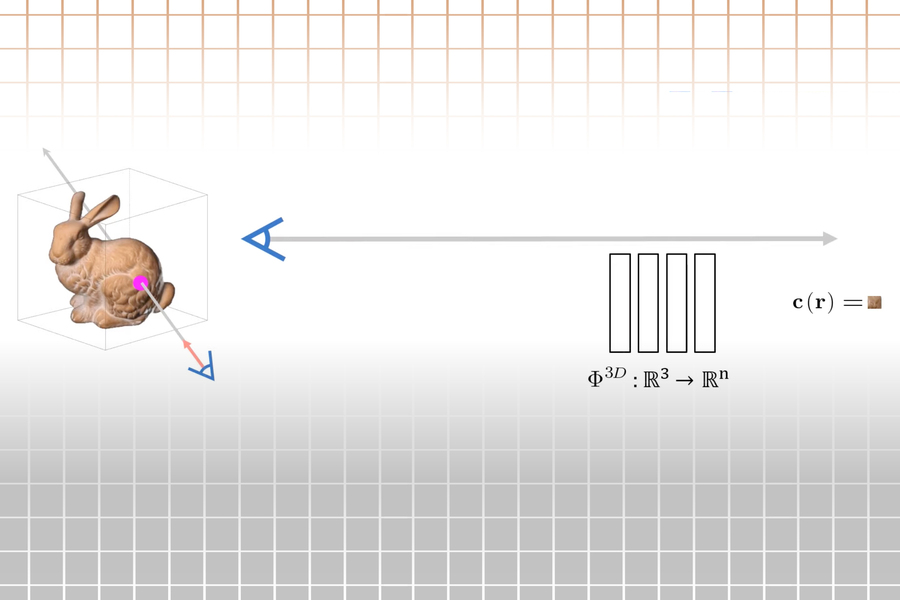

This innovative approach transforms how machines perceive spatial environments by representing scenes as comprehensive 360-degree light fields—mathematical functions that capture all light rays flowing through every point in 3D space in every direction. By encoding these light fields into specialized neural networks, the system enables dramatically faster rendering of underlying 3D scenes from single images.

The light-field networks (LFNs) developed by the research team can reconstruct complete light fields after observing just a single image, enabling real-time 3D scene rendering at frame rates previously unattainable with traditional methods.

"The ultimate promise of these neural scene representations lies in their application to vision tasks. You provide an image, and from that image, the system creates a representation of the scene. Then, any reasoning you need to perform happens within that 3D scene space," explains Vincent Sitzmann, a postdoc in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and co-lead author of the research paper.

Sitzmann collaborated with co-lead author Semon Rezchikov, a postdoc at Harvard University; William T. Freeman, the Thomas and Gerd Perkins Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and CSAIL member; Joshua B. Tenenbaum, a professor of computational cognitive science in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and CSAIL member; and senior author Frédo Durand, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science and CSAIL member. This groundbreaking research was presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

Advanced Ray Mapping Technology

In computer vision and graphics, rendering 3D scenes from images involves mapping thousands or even millions of camera rays—imagine laser beams emanating from a camera lens, with each ray striking a single pixel. These computer models must determine the precise color value for each pixel struck by every camera ray.

Most current techniques accomplish this by taking hundreds of samples along each camera ray's path through space—a computationally intensive process that results in sluggish rendering speeds.

In contrast, an LFN learns to represent a 3D scene's light field and then directly maps each camera ray within that field to its observed color. LFNs leverage the unique mathematical properties of light fields, which enable ray rendering after just a single evaluation, eliminating the need for multiple calculation points along each ray's path.

"With conventional methods, rendering requires following each ray until you find a surface. This involves thousands of samples just to identify surfaces, and even then, you're not finished because of complex phenomena like transparency or reflections. With a light field, once you've reconstructed it—which is itself a complex problem—rendering a single ray requires just one sample of the representation, because it directly maps each ray to its color," Sitzmann elaborates.

The LFN classifies each camera ray using its Plücker coordinates—a mathematical representation that describes a line in 3D space based on its direction and distance from its origin. The system calculates the Plücker coordinates of each camera ray at the point where it intersects a pixel to render the final image.

By mapping rays using Plücker coordinates, the LFN can also compute scene geometry through the parallax effect—the apparent difference in an object's position when viewed from different vantage points. This phenomenon is observable when you move your head: distant objects appear to move less than nearby ones. The LFN leverages parallax to determine object depth within scenes, encoding both geometric structure and appearance.

To reconstruct light fields effectively, the neural network must first learn light field structures. The researchers trained their model using numerous images depicting simple scenes with cars and chairs.

"Light fields possess intrinsic geometric properties that our model aims to learn. One might worry that light fields of different objects like cars and chairs are too dissimilar to find common patterns. However, as you increase the variety of objects—as long as some homogeneity exists—the model develops a progressively better understanding of how light fields of general objects appear, enabling generalization across object classes," Rezchikov explains.

Once the model has learned light field structures, it can render complete 3D scenes from just a single input image.

Breakthrough Rendering Performance

The researchers evaluated their model by reconstructing 360-degree light fields of various simple scenes. They discovered that LFNs could render scenes at over 500 frames per second—approximately three orders of magnitude faster than alternative approaches. Additionally, the 3D objects rendered by LFNs typically exhibited greater sharpness and clarity compared to those produced by other models.

LFNs also demonstrate superior memory efficiency, requiring only about 1.6 megabytes of storage compared to 146 megabytes for a popular baseline method.

"Light fields were proposed previously, but they were computationally intractable at the time. Now, with the techniques we've employed in this paper, we can both represent and work with these light fields effectively. This represents an exciting convergence of mathematical models and neural network approaches coming together for representing scenes in ways that enable machine reasoning," Sitzmann notes.

Looking ahead, the research team aims to enhance their model's robustness for complex, real-world scenarios. One promising direction involves focusing on reconstructing specific patches of light fields, which could improve performance and efficiency in practical applications, according to Sitzmann.

"Neural rendering has recently enabled photorealistic rendering and editing from only sparse input views. Unfortunately, all existing techniques remain computationally expensive, preventing applications requiring real-time processing like video conferencing. This project represents a significant leap toward a new generation of computationally efficient and mathematically elegant neural rendering algorithms," comments Gordon Wetzstein, an associate professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University, who was not involved in the research. "I anticipate widespread applications in computer graphics, computer vision, and beyond."

This research received support from the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, Mitsubishi, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the Singapore Defense Science and Technology Agency.