The global pandemic has accelerated the integration of artificial intelligence and robotics into our daily lives, with autonomous machines now performing critical functions like disinfecting healthcare facilities, transporting medical specimens, and facilitating remote healthcare services.

Recent surveys indicate a growing public acceptance of robotic assistance, with many individuals expressing preference for contactless options such as self-driving vehicles and automated delivery systems to minimize virus transmission risks.

As sophisticated autonomous technologies become more prevalent in public spaces, robotics experts Julie Shah and Laura Major advocate for a dual approach: redesigning robots to better integrate with human society, while simultaneously adapting our social structures to accommodate these new AI-powered assistants.

Shah, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT and associate dean of social and ethical responsibilities of computing at the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing, joins forces with Major SM '05, CTO of Motional—a self-driving car venture backed by Hyundai and Aptiv. Their collaborative work culminates in a groundbreaking publication, "What to Expect When You're Expecting Robots: The Future of Human-Robot Collaboration," released this month by Basic Books.

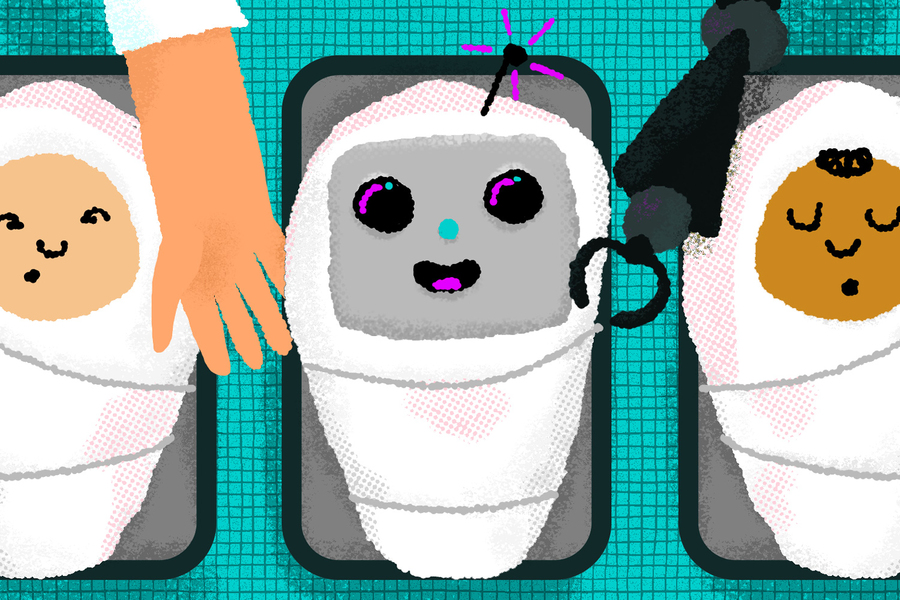

The authors predict a paradigm shift in robotics: future machines won't merely work for humans but will operate alongside us as collaborative partners. Unlike traditional industrial robots or domestic vacuums designed for controlled environments, next-generation AI systems will function in the unpredictable real world, requiring sophisticated human-robot interaction capabilities and mutual understanding.

"A significant portion of our book focuses on developing robotic systems that emulate human cognitive processes, particularly the nuanced social signaling that enables smooth societal functioning," Shah explains. "Equally important, we explore how our infrastructure—from pedestrian crossings to social conventions—must evolve to accommodate robotic entities effectively."

For robots to safely navigate public spaces, they must develop sophisticated comprehension of human social dynamics and behavioral patterns.

Consider a delivery robot navigating a crowded sidewalk: while it can easily avoid static obstacles like traffic cones or lampposts, encountering a person pushing a stroller while carrying coffee presents a more complex challenge. A human observer would recognize the social context and yield appropriately—but can an autonomous system detect and respond to such subtle cues?

Shah believes this capability is achievable. As director of MIT's Interactive Robotics Group, she's pioneering technologies that enable robots to understand and anticipate human actions, including movement patterns, activities, and social interactions in physical environments. Her research has produced robots capable of recognizing and cooperating with humans in diverse settings from manufacturing plants to hospital wards, with the goal of safely deploying socially-aware robots in unstructured public spaces.

Meanwhile, Major has been instrumental in developing practical autonomous systems, particularly self-driving vehicles, for real-world operation beyond controlled environments. Their professional paths converged at a robotics conference approximately one year ago.

"We were operating in parallel domains—myself in industry, Julie in academia—each independently championing the need for societal adaptation to intelligent machines," Major reflects.

That initial meeting planted the seeds for their collaborative book project.

In their publication, the engineering experts explore bidirectional adaptation: how robotic systems can better perceive and interact with humans, and how our urban environments and infrastructure might evolve to accommodate autonomous machines.

The authors cite San Francisco's 2017 experience with delivery robots as a cautionary tale. The sudden influx of autonomous delivery systems from tech startups created sidewalk congestion and posed unexpected hazards, particularly for elderly and disabled residents. The city responded with strict regulations limiting robot operations—enhancing safety but potentially stifling innovation.

To prevent similar scenarios, Shah and Major propose dedicated robot lanes, analogous to bicycle paths, to safely separate human and machine traffic in increasingly crowded urban environments. They also envision a coordinated traffic management system for robots, similar to aviation protocols.

The 1965 Grand Canyon mid-air collision prompted the creation of the Federal Aviation Agency and implementation of the Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS), which enables aircraft to detect and avoid each other independently of ground control. Similarly, the authors suggest that public robots could be equipped with universal communication systems allowing them to detect and coordinate with other machines, regardless of manufacturer or software platform.

"We might also develop transponders for humans that communicate with robots," Shah suggests. "For example, crossing guards could use smart batons that signal nearby robots to pause, ensuring safe street crossing for children."

The trajectory is clear: autonomous machines will soon populate our sidewalks, retail establishments, and residences. As their book title implies, preparing for this technological integration requires fundamental shifts in both our perception of technology and our physical infrastructure.

"Just as raising a well-adjusted child requires community support to realize their full potential, integrating robots into society demands collective effort," Shah and Major conclude.